Lately I've been doing some posts on the internal part of stories, the internal plotline and on balancing interiority. For a long time, I've wanted to write a post about when to lay on that interiority a little thicker in a story. This is an important topic because many of us were taught that writing the abstract is bad and that we shouldn't spend too much time in introspection.

Those are both true, somewhat.

Writing in the abstract can be "bad" because it's less immersive and therefore less impactful for the audience. It relates more to "telling" not "showing." It doesn't allow the audience to experience the story (generally speaking), and it gets way overused (and used poorly) by beginning writers.

In truth though, many of your character's inner pieces are going to be abstract.

I mean, they kind of have to be, because they exist inside the character.

And as I mentioned before, the internal plotline is the most abstract plotline, since it's about how a character arcs.

As for introspection, beginning writers do tend to write too much, and they tend to do it in "bathtub" scenes--scenes that happen largely in the character's head, but aren't usually moving the story forward. That can be a big problem.

There are so many nuances to this topic though, that I've frankly struggled on where to put today's info and how to organize it. My thoughts eventually evolved into this post and this angle, and I can only hope it was the best approach. (Though I acknowledge it won't click with everyone, and I'll be looking at this topic from a more advanced writing level.)

In any case, let's talk about when it might be a good idea to focus more on your character's interiority, on the page.

And to some extent, how much interiority you should include, will depend on what kind of story you are writing. . . .

Character-driven vs. Plot-driven

You may have heard there are character-driven stories and plot-driven stories. These are terms I don't use a whole lot, in part because I think they are a bit misleading, for reasons I'll likely cover in a future post. Regardless . . .

Character-driven stories focus more on the character. They focus more on the character's personal journey, how he is impacted by the events of the plot, and how he arcs through the narrative (because of his choices). These are stories that emphasize the internal plotline. A Man Called Otto and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty are character-driven stories.

Plot-driven stories focus more on the plot (obviously). They focus more on the external journey. Rather than emphasizing high personal stakes, they emphasize broad, far-reaching stakes. They are less about how the protagonist is impacted by the events, and more about how other people or the world at large is impacted by them. 007 and Ghostbusters are plot-driven stories.

There is more I could say about either of these categories, but we'll keep it simple for now.

And it's worth noting that many stories exist somewhere in the middle of these. This is all really more of a spectrum rather than an either-or situation.

Some genres fit more into one category than the other. Drama, women's fiction, and literary fiction are almost always character-driven. Thrillers, action films, and adventure stories are almost always plot-driven.

As you may have guessed by this point, character-driven stories are going to have more interiority than plot-driven stories.

So while a big chunk of introspection may be perfectly fine in women's fiction, another chunk of introspection the same length may be problematic in a thriller.

Furthermore, it also depends on what you've established as the baseline of interiority in your story. Is this a story where we are constantly getting a unique take on what is happening from a colorful viewpoint character? Or is this a story where we mainly get just enough interiority to provide context and validation for the audience? The sort of interiority we might expect from anyone in that same situation?

What you establish as a baseline will affect what you can get away with.

So this is a difficult topic to cover, because how much interiority you can lay on in a given place, is relative to the type of story you are writing.

This means it's not really a matter of word count. And it's arguably not even really a matter of percentage.

A lot of it depends on your story.

With that said though, there are some places where you can--relatively speaking--use more interiority. Let's go over those.

Internal Plotline & Internal Conflict

Okay, this may sound obvious, especially since I recently did a whole post about the internal plotline, but I'm going to cover some things from a slightly different angle.

In that previous post, I talked about how, at the basic level, a plotline should have these things: an objective, an antagonist, a conflict, and consequences (and a turning point).

An Objective

In the internal plotline, the objective is fulfilling an abstract want. Luke Skywalker wants to become, or be part of something great. Hamilton wants to build a legacy. Agent Mulder wants to find and reveal the truth. In order to write a great plot, these wants need to show up as concrete, measurable things--like Luke wanting to become a Jedi, rescue the princess, and destroy the Death Star. Or Hamilton wanting to win the war.

In any story, this abstract want is not being fulfilled (or if it is, it will soon be put in jeopardy). This is why the protagonist does whatever she does.

In most stories, it's okay to use interiority to convey the objective.

This isn't the only way to convey the objective. Certainly a character can voice in dialogue what she wants or aims to do. Or we can show or imply this in action. In fact, as I mentioned, we need this want to show up in concrete ways to tell a good story.

But if you are conveying the character's want . . . you can get away with a little more interiority.

Because it's an element that informs the plot and largely motivates the story. So writing about it will feel more relevant, and less like a superfluous passage that is distracting from the story (which kills pacing). Instead, it's contributing to, and bolstering what's integral to the story.

We may say that writing about the want is the equivalent of writing the "I want" song in musicals. These songs are in almost every musical--"Part of Your World" in The Little Mermaid, "My Shot," in Hamilton, "The Wizard and I" in Wicked, to name a few. These are in almost every musical because establishing what the protagonist wants is integral to a good story.

As always, though, anything taken too far can cause problems (and chances are, you aren't writing a musical), so you'll have to gauge how much is too much according to your story. Audiences also don't like a bunch of repetition, so you'll have to dig deeper into that abstract want so you aren't just repeating the same thing over and over. You'll likely want to get into why the character has that want and how they believe fulfilling it will make their life better (and perhaps what it's like to live without that want fulfilled).

I also need to mention that not all characters are consciously aware they have this abstract want driving them. For them, it could be totally subconscious. In that case, the character is going to focus much more on the concrete goal in their thoughts, rather than this abstract want. And in either situation, the character believes achieving this concrete goal will largely satisfy them. Focusing their introspection on the concrete goal likewise strengthens the story, because it bolsters the first element of (the external) plot--the goal itself.

The audience gets a stronger sense of what achieving this goal means to the character, and so the audience gets more invested in the story--they'll want to stick around to see if the goal gets achieved, and the interiority won't feel so out of place.

Antagonist & Conflict

The next two elements have a similar effect because they both relate to plot. Introspection isn't usually meant to be random--that's when we run into issues--it's meant to contribute to the story, to enhance the story, and to move the story forward.

When the character is acting as an antagonist to himself, and therefore creating internal conflict, you can include more interiority.

Because it's relevant to the plot.

I know I'm kind of talking in circles, but that's the main point here--if it's relevant to the plot, then it's relevant to the story, and you can layer more on.

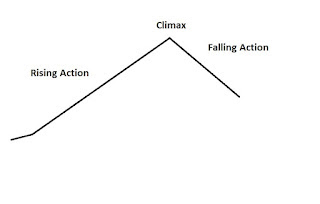

I've talked before about how all structural units fit this basic shape.

It's a fractal, so smaller versions of it exist inside the overarching version.

It's the shape of acts.

And it's the shape of scenes.

When a character runs into an antagonist, it creates conflict. This escalates us into the rising action.

If the rising action--the conflict--of a scene is largely internal, then yes, of course you can use more interiority. Because the driving conflict is happening inside the character.

Now often it's also useful and more impactful if it shows up in concrete ways. For example, a character in conflict about whether or not to ask a coworker on a date, may pick up the phone to do that, then slam the phone down out of fear. Then pick up the phone, redial, only to ask the woman if she saw the email from their boss before hanging up again. Then maybe he calls again, says something stupid, and has lessened his chances with her.

The character is an antagonist to himself, but his internal conflict is also impacting the concrete world. That's often ideal.

In any case, you are justified in using more interiority, because the antagonist is the self and the conflict is with the self. That's where the tension is, that's where the escalation is, that's what is interesting.

As I mentioned before though, not all internal conflict is related to the internal plotline. And that's okay. Sometimes it's related more to the external plotline or even a relationship plotline. Sometimes the character is simply conflicted about which action to take next on their adventure. Should they team up with a questionable thief? Or go to their estranged father for help?

Even if it's not strictly related to the internal journey (or character arc), you can still get away with more interiority when there is internal conflict about any relevant situation. (And usually "relevant" means it's related to one of the other dominating plotlines.)

Consequences (& Turning Points)

The turning point is that climactic peak in basic structure. It's when the current conflict is resolved, for better or worse. It's when we tip from conflict into consequences.

In the overarching internal plotline, the consequence is the character arc.

Anytime you are working with the character arc, you can use more interiority.

But again, you can overdo it.

And again, to be most effective, it should (also) show up in concrete ways.

It's not enough for me to read that Scrooge has changed, I need to see his change in concrete ways--I need to see him spend his money on others and visit Tiny Tim.

But if you want to delve deep into how this change impacted his mind and body as he completed his arc, and how it continues to impact him moving forward, that's likely going to be acceptable (as long as you don't wear out your welcome).

When working with smaller structural units (like acts and scenes), what happens after the turning point is going to show up in a slightly different way (though often that way is still relevant to the character arc). I'll talk about that way in the next section.

Let's first go more into consequences in general.

With consequences, I like to split them into two categories: ramifications and stakes.

Ramifications are the consequences that actually happen (like I just talked about). And stakes are the consequences that could happen. Stakes are what the character (or audience) thinks will happen when a certain condition is met. This means that stakes often fit into an "If . . . then" statement:

If Luke doesn't destroy the Death Star, the Rebel Alliance will be defeated.

If Hamilton doesn't come clean about his affair, Burr may use the information against him as a political opponent.

Those are stakes.

A full rundown of stakes is beyond the scope of this article. But the point I want to make here is you can use (more) interiority, when it relates to the stakes.

In fact, often stakes are conveyed through introspection. The viewpoint character clues the audience into the stakes, by laying them out on the page through their thought processes. If I don't defeat the [antagonist], then my family will be killed, the protagonist may think.

And having them think about the stakes will actually bring in more tension and hooks, which are just going to strengthen the story.

Of course, though, there are others ways to communicate the stakes, like through dialogue or by showing the consequences happen to someone else.

But you can definitely use more interiority when it's related to the stakes.

In the "Valleys"

If we view basic story structure as a fractal, we see that a story isn't made up of one continuous climb, but rather, smaller "peaks" and "valleys," in acts and in scenes.

I've mentioned how the rising action is where escalating conflict takes place and the peak is the turn where that conflict gets resolved (for better or for worse, and if only temporarily). This leads us into the consequences.

Well, the consequences are what the characters react to.

And another simplistic way of looking at this basic structural shape, is that the climb is where action takes place, and the fall is where reaction takes place.

After a turn (the peak), things should have changed (because there were consequences). In the falling action, the characters react to what just happened and the consequences they now have to deal with.

Some turns are bigger than other turns.

The turn of the whole story, the climax, is bigger than the previous turns of the acts.

And the turn of an act is going to be bigger than the turns of the scenes.

The bigger the turn, the bigger the consequences.

The bigger the consequences, the bigger the impact on the characters, which means the bigger the reaction.

The more important the reaction, the more important interiority can become.

If the protagonist just had her best friend killed at the turning point, then you're likely going to want to use more interiority to show how she reacts to such a blow. This is a place where you may want to lay more interiority on.

In the "valleys," the character reacts and eventually regroups (well, in most valleys--in some valleys the character has gotten what he wants and just enjoys that until a new antagonistic force appears.) The character will eventually come up with a new way forward and a new plan. You can use interiority to guide the audience through that thought process.

This will then lead us out of the valley and into the next climb.

One thing I want to mention here is that often one of the significant differences between character-driven and plot-driven stories, is the size of the valleys.

In a plot-driven story, the valleys are shorter . . . or I guess . . . shallower. We get a brief reaction (at least enough to validate the character isn't a robot), and shortly after, a new plan, and the plot moves forward.

In a character-driven story, the valleys are bigger . . . or I guess . . . deeper. We spend more time on the reaction and how the character eventually regroups.

Generally speaking anyway.

What happens in the valleys can also relate to character arc--how the character reacts to the turn can shape who that character is becoming.

. . . Okay, so I know what some of you are thinking right now, Well, September, at this point haven't you just told us we can use more interiority at basically any part of the story? That's a fair observation, so let me speak to that.

When Not to Wax Strong on Interiority

One of the points I'm trying to make through all this, is that what the interiority is about, matters. And this is where many beginning writers go wrong, and we start getting all these rules that we shouldn't use interiority very much.

Just as we can't write random things to make a good plot, we can't usually write random stream-of-conscious stuff and justify that the interiority belongs in the story.

One of the major problems that comes up here, is that the writer wants to use interiority to give an info-dump about how the character got to where she currently is and what happened in her past, and the writer mistakenly thinks that putting in random detailed thoughts about whatever comes along in the story creates "character." But true character is shown through the plot elements. It's not a long passage about the protagonist's favorite music, or a random flashback about how grandma always made her lemon cookies in the summertime. It's how the character acts and reacts to the plot. That's what shows us who she truly is (and/or who she is becoming).

I'm not saying you can't ever mention your character's favorite song. You can, if you can slip it into the scene without detracting from important things (or from pacing). And you can if you make it important to the plot.

It's not a good idea though, to spend a whole paragraph on your character's favorite bands, if it's not feeding into or overlapping with these plot elements.

In some stories you may be able to get away with this, if it suits the strong narrative voice. Sure, someone like Lemony Snicket can go on a tangent about driver's licenses when it's rather irrelevant, because that's why readers read his work. That's the main appeal of his books. But that is a very, very small percentage of literature.

What the interiority is about matters.

Okay, so, I know this article has been kind of heavy, and likely difficult for some of my readers to follow--that's all right. I don't expect it all to click with everyone, nor to click with everyone instantly.

But I've felt strongly this is an important topic to cover.

Because lots of interiority isn't always bad.

Improper use of interiority is bad.

It needs to be strengthening the story.

Not detracting from it.

Unfortunately, though, these aren't concepts you can easily whip out and share with new writers. You need to understand stories at a much deeper level before you can discern and apply these principles in the ways I've laid out (which is why I've been struggling with how to approach this topic).

So yes, limiting introspection is great advice for new writers, for most stories. Basic general statements about it, are helpful.

But as you understand the craft more, you understand it's all more nuanced.

In any case, I've done my best to explain these nuances today. Hopefully there is something in here that is useful to you.

Superstars Writing Seminars

Next month I'll be teaching two classes at Superstars Writing Seminars in Colorado Springs (Feb. 6 - 9th). This is a business-focused writing conference, but there are also some craft-focused classes (like mine).

I've been given a code that will get anyone who wants to join us, $100 off. Register here as a new member, student, or military, and use code SEPTEMBER2025

You can learn more about Superstars, and see the schedule at superstarswriting.com

Here is a brief summation:

Superstars Writing Seminars teaches writers the business of being successful in the publishing industry. Instructors are chosen from the top of the industry and include International Bestselling Authors, Top Editors, Indie Publishing Platform Managers, and many more. The primary goal at Superstars is to teach you how to have a successful writing career by sharing how those at the top of the industry manage their careers.