A character arc is how a character grows or changes through a story. At the most basic level, there are four types of character arcs: change positively, change negatively, remain steadfast positively, or remain steadfast negatively. Any other character arc should be able to--theoretically--fit into one of these four types. This article will go through each, while also giving examples and variations, and talking about common misconceptions.

While I've discussed character arcs on my blog before, including breaking down these four types, I've been missing an article that focuses solely on them to refer readers and clients to, so . . . I figured it was time. 😊

When you understand the different character arcs, you'll be able to understand your protagonist better and write a stronger story for him or her. You'll also be able to write stronger antagonists and Influence Characters, as well as better side characters. Because character, plot, and theme all interconnect, you'll also be able to write better plots and themes, too.

What is a Character Arc, Really? And How Does it Work?

Earlier I defined character arc as "how the character grows or changes through a story." Well, I lied.

Okay, it's more of a half-truth. That's a simplified definition.

For one, it's really more accurate to say "because of the story." One of the important things to know is that, like theme, a character arc shouldn't be superimposed on a story. It comes out of the story.

The protagonist should have a want that manifests as a concrete goal (yes, even if he's not typically "goal-driven" at the beginning). As he pursues the goal, he encounters antagonistic forces, which creates conflict. This leads to a struggle. As the antagonistic force is creating more and more conflict, the protagonist struggles to rise to the occasion. (This is why it's so important to have a strong antagonistic force.) How the character responds to the struggle creates the character arc.

Usually, the plot should have stakes, costs, and crises powerful enough that they push the character to his or her limits--they push the character to change or grow (of course, there are a couple of rare exceptions). And how he does will put a value on a worldview or belief system.

Now, often in the writing community, the term "character arc" is used to refer to any kind of change or growth a character has. It's a term that gets used rather broadly. Maybe the character had to build up his muscles, so he could fight the villain. Or maybe she had to learn to stop stealing.

While I won't argue that these are, in some sense, certainly "character arcs," it's usually more effective in storytelling to zero in on a dominating, thematic arc. THE Character Arc, if you will.

THE Character Arc is something internal. It's the internal journey that typically comes because of the external journey.

It will represent a worldview or belief system, which ultimately the story will put some kind of value on.

For example . . .

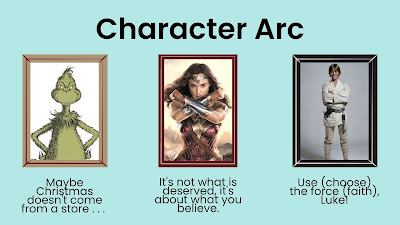

In How the Grinch Stole Christmas, the Grinch changes his worldview of Christmas when he realizes that Christmas doesn't come from a store.

In Wonder Woman, Diana believes we should fight for the world we believe in and proves this true at the climax of the movie.

In Star Wars: A New Hope, Luke comes to rely on faith (the force) instead of technology.

In Harry Potter, Harry learns that love is the most powerful magic in the world.

In 1984, Winston comes to embrace the seeming goodness of doublethink illustrated in the Party's slogan ("War is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength").

Each of these arcs serves as THE Character Arc in that they imply, represent, or state outright a worldview or belief system.

This is thematic in that it also feeds into an argument about how we should live our lives. We should understand that Christmas is about more than materials, we should recognize that relying on faith is sometimes more effective, and we should be wary of the power of doublethink--both within ourselves and in societal powers.

These are arguments that are present from the beginning of the story to the end of the story, and they are represented by the protagonist's internal journey, because of the plot.

These are THE Character Arcs.

And usually the most important character arc will come from the protagonist. However, other key characters can (and will) arc as well. And while some in the writing community argue that not all protagonists arc, I think you will find that essentially every protagonist will fit into one of these four basic arcs. . . .

4 Kinds of Character Arcs

So, there are two ways internally your character can grow.

1. They can change their worldview or beliefs.

2. They can grow in the resolve of their worldview or beliefs (remain steadfast), becoming more of something.

Each of these can happen in one of two ways.

1. Positive (becoming someone better)

2. Negative (becoming someone worse)

While people have different approaches and breakdowns of character arcs, when boiled down to the most basic level, there are these four: change positively, change negatively, remain steadfast positively, remain steadfast negatively.

. . . Now, some in the writing community argue that there are really only three basic arcs: change positively, change negatively, and steadfast.

I feel that this is a limiting perspective. The reality is, a steadfast arc usually is positive or negative. I think we can all see the difference between Wonder Woman's arc and Cruella's arc. They are both steadfast, but they are clearly on different trajectories. Wonder Woman is becoming a hero, while Cruella is becoming a villain. But I'll talk about this more below.

The Change Arcs

A change-arc character will do a 180 flip (more or less) from the beginning of the story to the end of the story. This is a flip that embodies a belief system.

The Grinch starts off hating Christmas, but comes to love and embrace it once he fully understands it.

In Frozen, Elsa believes in isolating herself to keep loved ones safe, but comes to learn that being open to others produces the most authentic form of love there is (even if it means getting hurt sometimes).

Each of these characters does a direct flip in their belief systems.

Positive Change Arcs

Negative Change Arcs

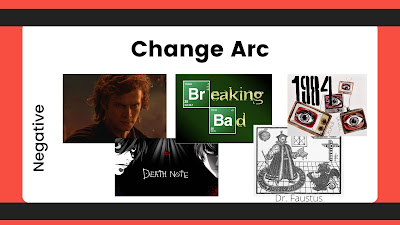

In a negative change arc, the character will flip into a worse, or more misled, person.

This works as the opposite of the positive change arc.

The character often starts as a morally good individual, more or less. She may have wholesome, upright, or even accurate views of life or a promising trajectory. But when faced with the struggles of the plot, she responds by making the wrong choices (usually putting her own wants ahead of what is needed), and gains a weakness, flaw, misbelief, or lie.

The character is often given the opportunity to become someone better--to choose better--but ultimately uses her agency to embrace the "dark side" or an inaccurate worldview. The character is unwilling or unable to let go or sacrifice this flaw or misbelief, leading to a sort of damnation.

For example, in Death Note, Light starts out as a very intelligent high school student, with a bright future ahead of him. But his boredom leads him down a path of self-damnation as he uses a supernatural notebook to begin killing off criminals. Before long, he begins to envision himself as a god of a new world--where he decides who lives and dies. But on the journey, he soon finds himself killing innocents. In the end, his adversaries prove that ultimately, he's nothing better than a serial killer.

In 1984, Winston starts out wisely, though secretly, aware of the lies and deceptions of Big Brother and the Party. While he may not always be able to articulate it, he knows the truth. He knows reality isn't what the Party says it is. But when he is imprisoned, he is ultimately tortured until he embraces the lie. At the end, he personally uses doublethink, and becomes fully converted to the Party's slogan. He comes to love Big Brother.

1984 may have a bit of a variation in that Winston doesn't really have much of a choice, but at the most basic level, his is still a negative change arc.

The Steadfast Arcs

A steadfast arc is also known as a "flat arc" or even sometimes a "growth" arc. Instead of doing a direct flip, the steadfast character will be, more or less, the same at the beginning of the story and at the end of the story. Instead of flipping, they usually become more of something. Instead of changing, they grow in the resolve of their beliefs.

Some steadfast characters remain virtually the same, such as 007. But today, many steadfast characters (especially protagonists) will grow by degree. She or he will gain a deeper, more refined understanding or a greater ability or more experience.

This doesn't necessarily mean the steadfast character never wavers or never has doubts or never meanders a different direction during the story. He or she just doesn't do a direct flip.

Positive Steadfast Arcs

In a positive steadfast arc, the character will start out with an accurate worldview or belief. She may be, more or less, morally good, wholesome, or upright. However, this doesn't mean she doesn't have any personal shortcomings, tendencies, or struggles. What the beginning of this arc really means, is that she understands how reality or the world works, accurately. She understands the truth.

Through the story, her beliefs will be challenged and tested. Other forces may try to get her to adopt a different worldview or lifestyle, but ultimately at the end, she upholds her initial worldview and proves it true to those around her. She stays committed, steadfast, to who she was in the beginning.

In Wonder Woman, Diana begins the story with the worldview that we should fight for the world we believe in. Even though the atrocities of war test her belief, and Ares tempts her to embrace a new perspective (that we should allow humankind to suffer the world they deserve), she ultimately upholds her initial belief at the end, and proves it true to not only Ares, but others around her. While she struggles and wavers through the middle, at the end of the story, she holds the same beliefs she had at the beginning of the story.

In Arrival, Louise Banks, a linguist, believes that communication can be key to avoiding conflict. As the world tries to deal with the aliens that have landed on Earth, everyone around her seems to dismiss the value of communication, or at least misunderstand its significance. At the end, she saves the world from war through communication (thanks to her linguistic background) and changes those around her in the process. Internally, her beliefs at the beginning are the same at the end.

Worth noting is that often in stories that feature positive steadfast protagonists, the world or supporting characters will do a direct flip. Instead of the protagonist changing internally, he helps those around him change for the better.

Negative Steadfast Arcs

In a negative steadfast arc, the character will start out with an inaccurate worldview, weakness, flaw, misbelief, or lie, and refuse to let it go. In fact, it may be helpful to think of those in this arc as "stubborn" rather than "steadfast."

This is a character who probably should complete a positive change arc, if he is to become a better, more whole person, but instead, holds onto his inaccurate beliefs. Instead of coming to the truth, he holds fast to his initial ways.

The conflict will test the character's resolve to the inaccurate worldview, and he will cling to, or fully embrace it. Other characters may try to get the character to go another way, but this character is essentially on a "highway to hell."

Positive vs. Negative Arcs: To put it simply, positive arcs illustrate the thematic truths we should adopt into our own lives--the truths that will allow us to become better people and create a better world, by having an accurate understanding of reality. Negative arcs illustrate what happens when we embrace inaccurate worldviews--when people believe in a nonreality. Positive arcs lead us toward becoming "whole" or "complete" individuals, while negative arcs lead us into a sort of damnation. Positive arcs show what we should do. Negative arcs show what we should not do.

Character Arc Variations

The Disillusionment Arc

In a disillusionment arc, the character starts off with an inaccurate (and naive) worldview. Because of the conflicts in the story, he comes to the truth, which makes him sad, not happy.

Ultimately, the arc is about the truth--the accurate worldview or belief system--but sometimes what's true doesn't make us feel good inside. For example, I may discover tomorrow that my mother honestly hates me. It's a truth, but it doesn't make me feel good. It makes me feel bad.

The truth doesn't care about your feelings. It's true whether it makes you happy or sad or whether or not you like it.

In a disillusionment arc, the character realizes life is not as great as she thought. For example, she may come to learn that sometimes hard work isn't enough to get your dreams--there are things outside of your control, and that's the truth she realizes at the end.

In Hamilton, Hamilton eventually comes to the truth that he can't control his legacy, despite how much he tries. He has no control over who lives, who dies, or who tells his story.

Multiple people in the writing community categorize a disillusionment arc as a negative arc, because it doesn't leave you feeling good inside.

I personally categorize it as a positive change arc, because coming to the truth and understanding reality, is a positive thing and will get you further in becoming a better, more whole individual.

However you want to categorize it, just understand how it works.

Change Arc Variation

As stated above, often the change-arc character will do a big flip. She believes or embodies one worldview in the beginning, and then does a full flip into believing or embodying the opposite worldview. These two worldviews make up the thematic argument.

In some stories, it doesn't play out this way.

It's possible that the character doesn’t start the story with a worldview or opinion on the thematic argument (or central idea). They may not know the argument exists at the beginning of the story. Or, alternatively, they may know there is an argument, but they haven’t yet decided which side they believe in. In this sense, they start on “neutral.”

I actually feel like Luke Skywalker fits this variation. He's never even heard of the force, nor is he really aware that there is an argument as to whether we should rely on technology or faith. One may say he somehow represents the technology side, in that we see him in the beginning working with technology. But I feel like . . . he starts as a bit of a blank slate. Once the story gets going, we see he does have different feelings on this topic, and ultimately, changes his worldview to rely on faith (the force). So, I would still consider him a positive change character, even if he starts somewhat neutral.

Alternatively, in another story, we may show how people are arguing about whether to trust technology or faith in the beginning, with the protagonist aware of, but unsure of which worldview is accurate (the truth). In the end, he picks a side. Change.

Steadfast Arc Variation

The steadfast arc is often misunderstood in the writing community. The character holds the same beliefs at the beginning of the story and at the end of the story. But this doesn't mean she never struggles, questions, doubts, or wanders through the middle.

Some steadfast characters start and end with the same belief system, but will actually entertain an opposing belief system through the middle—usually the third quarter—of the story. This can sometimes be confusing when writers go to categorize their characters.

A good example of this happens in The Lion King. In the beginning, Simba believes in the Circle of Life--that there is a divine destiny and order in all living things. However, at the midpoint, Scar convinces him he killed his father, so he runs away, turning his back on his divine role. Under the influence of Timon and Pumba, he comes to act on the idea of "Hakuna Matata"--no worries = no divine order = no Circle of Life. Timon even openly says they have turned their backs on the world (read: on the Circle of Life). At the end of the middle, Simba must re-embrace his initial belief. He must come to the truth--he is the one true king, and must take his place in the Circle of Life.

(Check out "3 Categories of Steadfast, Flat-arc Characters" for more breakdowns of the steadfast arc.)

Multiple Character Arcs

It's possible for a character to have multiple character arcs, which can make them tricky to categorize. To make it even trickier, the arcs don't have to be the same type.

For example, Wonder Woman primarily has a positive steadfast arc, arguing we should fight for the world we believe in. But she also has a secondary change arc (a disillusionment arc) as she realizes humanity isn't black and white, it's gray.

Likewise, Simba has a steadfast arc in regards to the Circle of Life, but he has a positive change arc as well. He starts off irresponsible and must learn to take responsibility.

This also suggests there are multiple, prominent themes.

If you want to keep things simple, zero in on the arc that is most prominent for your character--this should also be an arc that is touched on at the climax (Wonder Woman ultimately defeats Ares by embracing her truth that we should fight for what we believe in, and Simba ultimately dethrones Scar because he stands by the Circle of Life).

With that said, you can totally flesh out each arc if you would like to.

Arc Confusion and Misconceptions

There are a few things you should be aware of when it comes to character arcs and the writing world.

Character Arc vs. Narrative Arc

Character arc entails all we've talked about in this post--the internal journey. However, you may have heard the term "narrative arc." A narrative arc is the path of the plot--the external journey. It's another way to refer to the story as a whole. Simba's character arc is about upholding the Circle of Life. The Lion King's narrative arc is everything that happens in the plot from Simba's birth to the birth of his cub. This is the whole story structure. In The Story Grid approach to writing, Shawn Coyne calls this the "Global Story." I've also seen this called a "plot arc."

Flat-arc Character vs. Flat Character

"Flat arc" is another term for a "steadfast arc." Some people confused the term "flat arc" with "flat character."

Flat-arc characters aren't necessarily flat characters. A "flat character" is a simple, two-dimensional character. Flat-arc characters can be just as round, or in some cases, even rounder, than some change-arc characters.

Often a change arc will help make a character feel rounder and more complex, but it's not the only way to make a character round and complex.

A flat-arc character can be a flat character, but it's not something that goes hand in hand.

To learn more, see "Flat Characters vs. Round Characters" and "Debunking 6 Myths about Steadfast, Flat-arc Characters."

"Flat-arc Characters are Bad" & "Every Protagonist Needs a Change Arc!"

I've seen some in the community express that writing a flat-arc/steadfast protagonist is bad, boring, or a mistake. This is far from the truth. Anyone think Wonder Woman, The Lion King, Princess Mononoke, Finding Neverland, Arrival, Cinderella, Legally Blonde are bad, boring, and mistakes?

The truth is, almost every story will feature a steadfast character, even if they aren't the protagonist. If it's not the protagonist, then usually it's someone the protagonist has an important relationship with.

I once even ran into an article that said it was bad to give even side characters steadfast arcs. Well, the reality is, it'd be almost impossible to give the whole character cast change arcs! We need flat arcs to produce great stories.

Along those lines, some insist that your protagonist must have a change arc! Spoiler: He doesn't have to.

Most protagonists are (positive) change-arc characters. They tend to be easier to write, and easier to write successfully. And truth be told, most writers are also taught to write (positive) change-arc protagonists. In fact, some approaches to storytelling will only guide you on how to write change-arc protagonists (which makes it difficult when you want to write a great steadfast protagonist). For example, the Hero's Journey often emphasizes a change arc. And Story Genius by Lisa Cron (fantastic book, by the way) is geared toward helping you write a change-arc protagonist. If you try to apply some of these principles to steadfast characters, you'll probably run into some problems.

To some, "character arc" = "positive change arc." It doesn't have to, but it's helpful to be aware of that mindset.

(If you need help writing a steadfast protagonist, I have several resources.)

Why Do Character Arcs Matter?

We've covered each basic type of character arc, as well as noted variations and misconceptions. Well, so what? Why does this matter?

I'll tell you. 😉

The character arc is the most important feature of your protagonist. Really? Really. It's easy to get hung up on all the superficial stuff--likes, dislikes, childhood memories, hair color and style, attire. But at the end of the day, the character arc is the most critical component of your character.

This is because it's influenced by the plot, and it influences the theme.

How the character responds to and addresses the conflict, leads to the character arc, and how the character arcs puts a value on a worldview or belief system, which informs the theme.

Of course, if you want to start a story with character, you need only choose an arc and select the sorts of conflicts that will lead to that arc. A change character must be pushed to change through the obstacles he faces. A steadfast character must have her resolve tested through the hardships she weathers.

Also, when you understand how your protagonist arcs, you can use that to help create other key characters in the story. Often if the protagonist is a positive type, the antagonist will be a negative type. And often if the protagonist is a change type, the Influence Character will be a steadfast type.

Finally, when you understand what arc your character has, you can use that information to enrich her inner journey--because you'll know where she's headed.

Love this info? It's part of my online writing course, The Triarchy Method. Learn more or register here.

I am very sorry to say that I have lost a quite big amount of faith in this blog given how you seem to think that Light Yagami changes for the worse... since when is upholding justice something bad? Since when is punishing evildoers something bad? Since when is protecting innocents something bad? What makes Light so compelling and beloved is that he's the type of antihero you don't usually see in manga, one with an incredibly strong moral code but who is also ruthless in pursuing his dream of a perfect world for all righteous people - which is evidently a noble goal. I don't know, but you seem to buy into Near's half-arsed response from Page 107 (which is a clear demonstration of his hypocritical amorality) while dismissing all the awesome points brought up by Light's speech just moments before... holding thoughts like this makes me think that the person proposing them is either amoral or immoral, if not outright an already violent criminal who opposes justice for the simple fact that he doesn't want to be punished.

ReplyDeleteIf anything, Light's arc could be seen as the steadfast positive arc, since he holds to his belief in justice until the very end, always refusing to lose his hope in humanity's potential for doing good even in spite of all the atrocious actions he knows they commit, instead choosing to guide them towards an ideal future. I really don't know how anyone could think that someone who stops all armed warfare and causes violent crimes to drop by 70% in the span of six years could be even remotely evil. Anyway, I apologize in advance for any linguistic mistakes that I may have committed, as English is not my native tongue.

Justice: the principle or ideal of just dealing or right action. (2) : conformity to this principle or ideal : righteousness. the justice of their cause. : the quality of conforming to law.

DeleteLight has no respect for the law or for justice, since he lacks mercy which is a component of justice. The criminals in prison were already being punished so their deaths were for the benefit of experimenting, not justice. Light was manipulative and abusive to the people around him and lacked basic human empathy. As the arc continues his primary concern is for himself, his glory and his outwitting the authorities.

Though violent crimes drop, the causes of crimes do not change. The idea that the threat of death would stop violent crime is also misguided, as many countries with capital punishment have high rates of violent crime. Without the constant threat from the death note, the world would go back to how it was, so in the long run nothing has changed.

Crimes on the innocent:

• Murdered the FBI agents

• manipulated Raye Penber into writing the names of his colleagues on pages from the Death Note. This is sadistic, to cause someone to kill their friends and colleagues shows how evil he had become.

• Murdered Naomi Misora to stop her from revealing how Light figured out Raye Penber's name.

• Psychologically manipulated and abused Misa Amane

• Mockingly asked Naomi Misora if she wanted his phone number to contact him even though she'd already been sentenced to her death by the Death Note purely for pleasure.

• Murdered the rest of the Yotsuba group, who wanted to redeem themselves after the Yotsuba Kira was arrested.

• Prepared to kill every member of the Task Force with whom he'd known and worked with for several years, taking sadistic pleasure in believing he'd be victorious

Light started out wanting justice but, in the end, it was the power over life and death and the misbelief that he was superior intellectually and would never be caught that drove him on. That is why his arc is a negative arc. He lost his humanity and the capacity to think about others in a meaningful way. In the manga it is much clearer that Light has fallen into darkness.

Hey, there! Sounds like you really know your source material. It’s just an example, and it’s fine if you disagree with it—the important point is that you understand the four different arc types. Not every example will fit everything exactly, but I would consider Light to be a negative change arc—and you’ll have to be disappointed with more than me over it, because I’ve also heard other writers in the industry categorize him the same way online and in class.

ReplyDeleteThere is nothing wrong with upholding justice—and I certainly don’t think it’s a bad thing to do. And I haven’t read the story, only watched it, so I’m not sure on the differences of the adaptation. But I feel that the thematic argument isn’t so much about *justice* as it is about how we *enforce justice.* After all, his antagonists are detectives that are trying to *uphold justice* and *also* “make the world a better place” by capturing him. So to me, this indicates that this is more of an argument about the methods, and do the ends justify the means? In this, I would personally say he does embody the negative arc because his methods are ultimately not proven to be “true,” “correct,” or “accurate” at the climax. At the climax, I feel that Near’s ideas are proven to be “the truth,” in how the climax turns the story and the conflict is resolved (as well as in the overall tone). I feel that the show shows that ultimately, despite all he’s done and accomplished, Light is another serial killer, and the ends don’t justify the means. The idea that one person (Light himself) should be the god of a new world and be the one to decide who lives and dies, I feel is proven false. I feel the story says justice is better upheld through other avenues. So, I feel it is an argument about who and how that should be done. Should the power go to one individual? Should the punishment always be death? Is it worth killing innocents along the way to make that happen?

Light is willing to kill and/or use even those in love with him—even his own family members. And he feels no true remorse for it. So yeah, I personally would consider that a moral problem. But regardless, the negative arcs aren’t always about . . . what’s “evil” so much as they are about what’s “inaccurate” or “untrue.” Sometimes in the community, we talk in “evil” and “bad” and “immoral” terms to simplify and generalize the negatives (in my opinion). I sometimes do this too, because it’s a more familiar way of looking at things for most people. And it doesn’t mean you can’t value, like, or respect the character.

One could also argue that there are multiples main themes, and Light embodies a different kind of arc for a different theme. But I feel that the primary theme is about the way justice is dealt, and I feel that within this argument, Light’s approach is proven false at the climax. Of course, this is going off the show, which could have very well manipulated the arc, and feel free to disagree. Heaven knows I’ve disagreed with plenty of examples in my life.

I've recently finished reading Story Genius and I felt the same way as you. She does mention that you can use it for negative change arcs as well and gives a few pointers here and there, but mostly it's about positive change arcs. I've been trying to find ways to apply its concepts to a negative or steadfast arc. It would be a great topic for a post... ;)

ReplyDeleteThat is probably true. I should maybe revisit that one when I get the chance. It is such a great book, and I'm sure I'd have more insight now, if I went back and looked at it again.

DeleteGreat information and was very helpful. Didn't know so many character arcs existed before reading this blog!

ReplyDeleteGlad it was helpful. Thanks for commenting :)

DeleteWhen was this article published? I'm referencing it for an essay :)

ReplyDeleteMay 23rd, 2022

Deletethank you for this detailed explanation! Absolutely loved reading it, and am using it to write my novel now. Sending love!

ReplyDeleteHi Soundarya,

DeleteI'm so glad it was helpful! I hope the writing goes great!

Hello, this is my first time i think commenting on any sorta blog or whatever it's called. I dont usually do this but I was in desperate search of a better understanding of character arcs as I'm actually trying to make a comic and hopefully one day (atleast its my dream job) write for a living, although probably for film and comic books or graphic novels specifically. I've found this information incredibly helpful and it's filled me with a bit of excitement. As I write this, I'm listening to music and letting ideas run in my mind, with now a better sense of what to do with them in terms of my ideas for characters and their arcs thanks to this blog. I hope I begin to make progress soon, although sometimes it takes me a while to come up with something for the characters and even overall narrative and want to stick to it with absolute certainty. Hopefully that'll change soon.

ReplyDeleteWell, thanks for commenting. 😊 I'm so glad this info was helpful. There are other approaches, but pretty much any character should be able to fit into one of these. I hope the inspiration keeps flowing, and you find success in your endeavors.

Delete