Writing a "bathtub story" is rarely a good idea. It often fits right up there with flashbacks; most of the time you shouldn't use them, but in certain circumstances, you can get away with them. Bathtub stories lack immediacy and as such, often bring the narrative to a grinding halt.

Yet they are common for new writers to write. So let's go over them, why they're a problem, how to fix them, and when to use one (if you dare 😉).

What is a "Bathtub Story"?

The term "bathtub story" originates from author Jerome Stern, who talks about them in his book, Making Shapely Fiction. He writes:

In a bathtub story, a character stays in a single, relatively confined space . . . While in that space the character thinks, remembers, worries, plans, whatever. Before long, readers realize that the character is not going to do anything. . . . The character is not interacting with other people, but just thinking about past interactions. Problems will not be faced, but thought about.

A bathtub story is essentially a story that takes place in introspection.

While most novels won't literally be an entire bathtub story, many new writers have bathtub scenes or chapters, where the character simply reflects and doesn't do anything meaningful. While Stern likens this to someone in a confined tub, I would argue these can happen even when the character is moving. The character may be taking a walk or washing the dishes, but the story elements only exist in her head.

Why Bathtub Stories are Problematic

Bathtub stories are a problem because all the interesting stuff is in the character's mind (if there is any interesting stuff). This brings in several issues.

1. The Story isn't Moving Forward

Because the bathtub story happens in a character's head, the character isn't taking action. Instead, she's likely ruminating on the past. While you can have a characteristically lazy protagonist, when it comes to the actual plot, all protagonists need to be problem-solvers. And not just in thought, but in deed. A true protagonist is a driver of the story. She must be actively trying to solve problems (that come from antagonistic forces and conflict). Otherwise, she is a passive victim or passive observer (in which case, she probably isn't the true protagonist, but just a viewpoint character).

If she's not problem-solving, the plot probably isn't moving forward. The protagonist should be in the concrete world, taking action or revealing important information, creating turning points. She should have a goal, and a plan, and should be pursuing them--even if the goal is to avoid something.

When she's stuck in her head, she may be thinking about her problems (or past experiences), but she's not influencing the trajectory of the story.

If she's not acting, she's also not completing a meaningful character arc. A character arc shouldn't be superimposed on a story, it should happen because of the story. How the character responds to meaningful antagonistic forces (which includes how she tries to solve problems), creates the character arc. The antagonists challenge her to change, or test her resolve. That can't really happen if she's not doing anything.

At the end of the bathtub scene, ask yourself: Has the protagonist's goal or plan shifted? Has her belief system been challenged or tested by antagonists?

If the answer is no, you likely haven't progressed the story.

2. The Character doesn't Demonstrate Agency

The protagonist needs to be making meaningful choices. For those choices to be impactful, they will be shown by the character taking significant action or revealing important information. Otherwise, his choice never leaves his skull, and therefore doesn't actually matter. So what if he thinks about what he wants to do? Real decisions will be shown.

We all think about things (goals, plans, or otherwise) that we don't actually pursue. If someone thinks about fixing your leaky roof, but never shows up, who cares? If someone thinks they can help with your relationship problems, but never reveals any advice, does it matter? Not really.

Because the role of the protagonist is to be a driver (and not just the antagonist's passive victim), he needs to act on choices to try to achieve goals and solve problems (which helps move the story forward).

Many writers mistakenly think that making the protagonist a passive victim makes him more sympathetic and likable. In reality, the opposite is true. An active protagonist who demonstrates agency is more sympathetic, because he carries some level of responsibility and accountability for any negative outcomes that happen (plus, he also shows us how badly he wants his goal). We all have random crap happen to us. It's more painful and sympathetic when well-intentioned choices lead to heartbreak. (For more on this topic, scroll down to #4 on this post.)

Not demonstrating agency, again likely means the plot or character arc isn't moving forward (and that your protagonist isn't interesting.)

3. Lack of Immediacy

With the "interesting" stuff happening in the character's head instead of concretely, the bathtub story lacks immediacy. The story isn't unfolding for the audience, and because the character is confined to introspection, she's not impacting anything at hand. A lack of immediacy almost always means a lack of tension. If there isn't a current threat, there isn't potential for problems to happen.

4. Focuses on the Past

Speaking of a lack of immediacy . . . bathtub scenes almost always segue into one or more flashbacks, which are likewise frequently frowned upon. Bathtub scenes at least usually focus on the past (even if there is no official flashback.)

Writers tend to look at the past--how the character got to where he is now, or how the current situation came about. While that can be meaningful for the writer, it's often boring for the audience. Or at least less interesting.

The past has already happened. You can't change it. What the character or antagonist does now, won't influence what happened then. (Well, unless you are writing a time travel story, but let's assume you're not).

Instead, the audience wants to be in the present, which holds more tension (or it should, if you've set up your story right). In fact, they actually prefer to lean into the future on a regular basis. The future hasn't happened yet, so it's more exciting, and what the character does now, will (or should) alter the future. While the audience likely can't verbalize it, they want you to imagine the different paths forward the story could go, and then convey them on the page. This is what creates stakes. Stakes are potential consequences. They are about what could happen if a certain condition is met. And what could happen is exactly the sort of thing that hooks and reels readers in.

Think about it. At the most basic level, hooks work by getting the audience to look forward to a later point in the story--to anticipate something they may read later (or soon). So, they keep reading.

You want to regularly lay out what could happen, and almost always in relation to the protagonist or antagonist. If the protagonist successfully does X, then Y will happen. If the antagonist successfully does A, then B will happen. Now the audience needs to see if the protagonist successfully does X or the antagonist successfully does A. (Or something of that sort.)

In fact, one of the few times visiting the past works well (including with flashbacks), is when doing so provides insight that could affect the future.

5. It's Abstract

If there isn't a flashback, then chances are the bathtub scene is full of abstracts and hypotheticals. The character is musing or even pontificating about the meaning of life, love, society, or what it means to be a homo sapien.

A story that is full of abstracts, often isn't as interesting. This relates to the "Show, don't Tell" rule. Stories are almost always more effective when they appeal to the senses and render a concrete world.

Even if you do want to write about love, it's usually more effective to "show" it, than tell it. (And if you tell it too much, in the wrong way, the story may sound preachy.)

6. Hurts Pacing

For all of the reasons stated above, the bathtub scene almost always leads to poor pacing. The lack of proper plot elements (and often, the lack of proper structure), paired with too much introspection focused on the past or abstracts, kills immediacy and brings pacing to a grinding halt.

If the story isn't going anywhere, then the reader is probably out before you can say "bubble bath." Maybe they'd rather watch paint dry and do their own pontificating in the tub.

Now that we've talked about all the problems, let's get into how to fix a bathtub scene!

How to Fix the Bathtub Scene

1. Get Out of the Bath

Bet you didn't see that one coming, did you?

Get the character out of the "bath" (or off her walk or away from the dishes) and put her where the action is. Or better said, where the true antagonist and conflict is (and that doesn't always mean a "bad guy" or a fistfight or shouting match (see links)).

2. Give the Character a (Current) Goal and an Antagonist

Give your character a current goal with a plan she can start taking current action toward. At the basic level, there are three types of goals: obtain, avoid, or maintain. Any of them is fine, as long as the goal has an antagonistic force opposing it.

Often big goals will break down into little goals, which turn into scene goals. So really, most scenes should have a goal for that scene.

The (scene) goal should be significant, meaning whether or not the character achieves the goal somehow shifts the direction of the story and influences what happens in the near future.

A goal to shave your legs in a bathtub or wash the plates probably isn't significant enough to merit a scene. It's unlikely those goals have the potential to shift the plot's trajectory or affect the character arc. (If they do, well, that might be a reason for a rule break.)

For a scene, the shift doesn't have to be huge, but it needs to be impactful enough to somewhat alter the protagonist's path forward.

The shift for an act should be bigger.

And the shift for the whole story should be huge (read: super impactful).

If you have a bathtub act or literally an entire bathtub book, you probably have a major problem.

3. Demonstrate Choices, through Action and Revealing Knowledge (Information)

As per #2 above, make sure your character is demonstrating agency. A choice doesn't matter if it doesn't leave his head. His choices should be shown in how he interacts with others and the environment. If he chooses to fix a leaky roof, he needs to actually get his tools and climb the ladder. If he chooses to give relationship advice, he needs to open his mouth and reveal his knowledge there to another individual. Thinking about it isn't enough.

4. Write in the Present

Do you really need that flashback or long introspection about the past? For most newer writers, the answer is no. If the info isn't contributing to the plot (how to get the goal, how to defeat the antagonist, how to resolve a conflict, or how to influence consequences), or the character's journey (her heart's deepest desire or her character arc), or the theme (what the story is exploring and arguing), then there is a 99% chance it doesn't need to be in the story. If it does affect those things, it may be worth including. Ask, does taking it out "hurt" or weaken one of those elements I listed?

If the past info really needs to be in the story, does it have to come through a bathtub scene? Is there a way it can come into the story other than straight-up introspection? Can it be "exposition turned into ammunition"? Can mentioning it contribute to the present, or better, the near future? Is there a way the story can be organized so that it happens in real time? Sometimes the flashback can actually be moved into the present by starting the scene or story just a little earlier (though this depends how far back in the past the flashback takes place).

Strive to focus on the present, and even mention the near future. Sprinkle the past in when it contributes to, and doesn't take away from, what is currently playing out.

5. Be Concrete

Show more than tell. (That's really all that needs to be said here.)

When to Use a Bathtub Story

With everything terrible a bathtub story brings in, is it ever a good idea to write one?

All rules are really more like guidelines and can be broken effectively, when handled with care.

In order to do that though, you have to understand why the rule exists, so you can downplay the costs that come with straying off the proven path.

So, now that we understand why the bathtub story is a problem and how you can fix it, let's marry what we've learned and talk about how to make one work.

1. You're Writing a Frame Story

A frame story is a story within a story. It will open with a character telling a story, and end with him finishing it. It's also possible that more than one story is told by the character.

The main story, is the story within the story, which essentially comes from the speaker's memory, so it is usually part of the past, as well as part of his mind.

I'm personally not a big fan of this method, but it does exist and can be useful in providing additional context for the main story. It's also usually more effective when the main story is affecting whatever is currently or about to happen to the speaker.

Obviously a frame story often acts as a sort of bathtub story.

2. The Antagonist is the Self, and this is Internal Conflict

A bathtub story or scene may work if the character is in (meaningful) conflict with himself. We are often cautioned against using a lot of introspection, but if a character is having internal conflict, then he both holds a goal and is also his own antagonistic force. This can be used to create a sort of rising action, as long as the proper plot elements are in place. It is a wrestle within the mind (or perhaps, between the mind and heart.) The climactic moment, the turning point, is the character coming to a definitive decision.

With that said, however, as Ross Hartmann points out in The Structure of Story, it's usually more effective to dramatize or "show" the internal conflict. Have the character take one action toward one outcome in one beat, and then an action toward the opposing outcome in the next.

But depending on where in story structure the internal conflict shows up, it may be handled better one way over another . . .

3. You're in the Falling Action

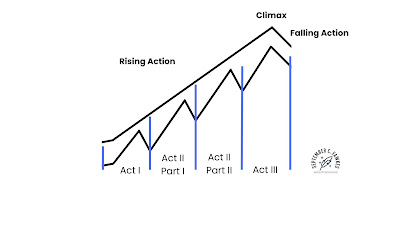

Story structure is a fractal. Not only should the story as a whole have a rising action, climax, and falling action, but inside of that, so should each act, and so should each scene.

During the rising action, the character should (almost) always be proactive. During the falling action, almost always, the character is reactive. She's reacting to whatever just happened.

If you are familiar with Dwight V. Swain's approach to scenes, this is essentially what he calls the "sequel."

At this point in the structure, it may not matter too much what the character is doing physically, what matters is how she is reacting, and then, what she decides to do next.

If you are in the falling action, it may be perfectly acceptable to write a (short) bathtub story.

4. It's Focused on the Future

As mentioned above, we are often cautioned against writing a lot of introspection. This is in part because writers often focus introspection on the past.

But when the introspection is focused on the future--what could happen if a goal is or is not reached and/or what the character plans to do next--then it becomes more relevant and more interesting. In fact, not only does it not take away from the story, but it can strengthen the plot. Introspection can be used well to lay out significant stakes. And, technically, this could be done in a "bathtub."

Just make sure having the character think about the future, leads to him soon taking action to try to influence it.

5. The Point is to Show Nothing is Happening

In rare, rare situations, the point of a scene may be to illustrate that nothing important is happening, and no changes are taking place. Such scenes almost never work (and if anything, are usually better conveyed in summary), but, someday, in some story, you may find yourself in need of such a moment. A bathtub scene might arguably work there.

Just don't make it longer than it needs to be to get the point across.

There are a couple of other times you may get away with a bathtub scene: if it's somehow contributing to theme, or if it's super entertaining or intriguing.

All in all, be cautious.

They fail more often than they succeed.

thanks for the posting of Bathtub stories. As a relatively new writer I found myself committing this crime and need to go back and 'fix them. I'll try harder, I promise.

ReplyDeleteHey Anon,

DeleteI think most of us committed this "crime" in the beginning, though I do hesitate to call it a crime. Is it a "crime" if the person doesn't know any better? For some reason, I think our brains just want to write this way!

Best wishes with the project.