I wish I'd known so many things as a beginning fiction writer. . . .

Recently, I was teaching and mentoring at the Storymakers Conference, and I got into a conversation with a fellow editor and writer about such things, and I've sort of been thinking about them off and on ever since. Thus, this post. But I'll keep this intro brief. . . .

Here are seven things I wish I'd known when attempting to write my first novel.

1. Nearly Every Scene Needs a Goal

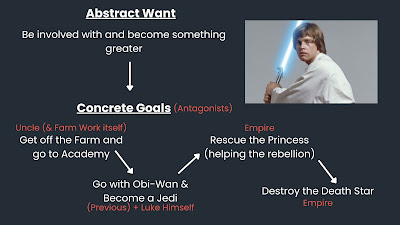

I consider goals to be the first element of plot. Without a goal, you can't have a true antagonist--because the antagonist is what opposes the goal. And without that, you can't have conflict. Or consequences. Or a true story.

But not only does your protagonist need an overarching goal for the act or whole narrative arc, but there should almost always be a little goal for nearly any scene. Often what happens, is the big goal will be broken up into scene-level goals. So, while Katniss's overarching goal is to win The Hunger Games, her scene-level goals may be to impress the Gamemakers, nail her interview with Caesar, or find Peeta in the arena. And of course, if there are multiple plotlines, as is often the case, there may be goals related to other plotlines beyond the main external one.

Admittedly (and unfortunately) though, even if someone had told me that 10+ years ago, I would have been very skeptical, and my mind would have immediately gone searching for scenes where there isn't a goal present.

I now realize, I had a very narrow view of what a goal was. See, when I heard the word "goal," I only thought of obtaining something. Thankfully, that is only one type of goal. Avoiding something can be a goal. And wanting to maintain things as they currently are can also be a goal--it just needs an antagonistic force (just as they all do).

So, at the most basic level, there are three types of goals: obtain, avoid, or maintain.

The goal can change. It can even be achieved or abandoned. In which case, a new goal needs to come into play.

Some scenes don't start with a goal, but usually one comes in as the scene progresses, and goals may not be a big component of sequel scenes.

There are, of course, some rare situations where there isn't really a goal at all, but when that happens, there is often still directionality--a sense of where the story is going.

Goals help tighten up the story by giving the audience a sense of direction, and if you don't have a goal in play, then you need to come up with another way to do that, such as playing with dramatic irony (the audience senses that the direction the story is going, is that the characters will eventually figure out what they already know).

Until a goal is in play, the audience can't really measure if what is happening is progress or a setback, and they can't get a strong sense of why what is happening matters (because the characters aren't trying to get anywhere specific).

Goals are super important in the overarching plot. They are equally important, if not even more important, within scenes.

2. Scenes and Acts Should Follow Basic Structure

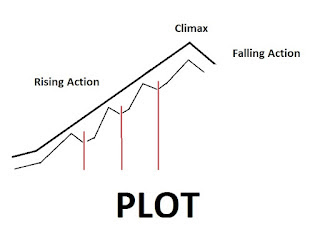

Most of us are probably familiar with basic story structure: rising action, climax, falling action.

But many of us weren't taught that this is also the basic structure of acts and scenes.

The difference, is that, in acts and scenes, it's smaller and less impactful.

This shape is a fractal that repeats itself within the narrative arc. It's like a Russian nesting doll, with the smaller structures of it fitting into the larger ones.

This means most of your scenes should actually have a climactic turning point.

This also means that the story should have changed at least a little because of the scene. How the story was at the beginning of the scene, should be at least a little different from what it is at the end of the scene. If it's not, the scene is probably just exposition and/or filler.

There are, of course, some exceptions to this. For example, sometimes the point of the scene is to show how things haven't or aren't changing. But if most of your scenes don't follow this structure and aren't changing the story at least a little, they probably aren't progressing the story, and are just filler (unfortunately!).

3. Know Your 4 Basic Character Arcs and Which You are Writing

Some writing advice doesn't work well for all stories, and that can be especially true when you get into character arcs. There are four basic types of character arcs: positive change, negative change, positive steadfast, negative steadfast. Any other character arc should fit into one of these four.

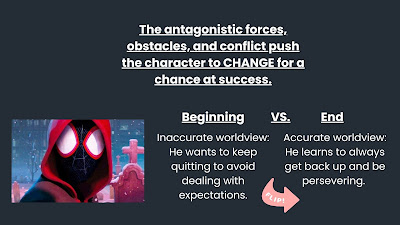

In brief, a change-arc protagonist will do, more or less, a 180-degree flip about a belief system or worldview. They go through a big change or transformation. If this is positive, the protagonist flips from an inaccurate worldview to an accurate one. If negative, the protagonist flips from an accurate worldview to an inaccurate one.

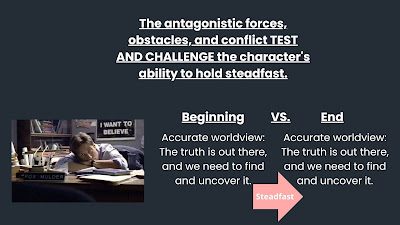

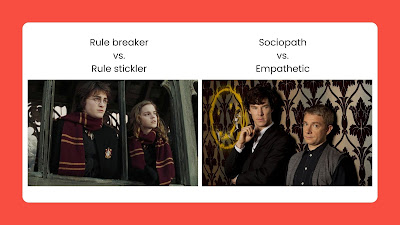

In a steadfast arc (also called a flat arc), the protagonist will stay, more or less, the same at the end of the story as they were at the beginning of the story. They will uphold the same worldview. A steadfast story is about the protagonist holding true to who he was in the beginning, despite other forces testing or tempting him to bend or quit. If this is positive, the protagonist is holding steadfast to an accurate worldview. If negative, the protagonist is holding stubbornly to an inaccurate worldview.

Of the four types, the most popular one is the positive change protagonist, which means there is a lot of great advice for that type. Unfortunately, that advice doesn't always translate well into the other three types.

This is where I ran into one of my biggest stumbling blocks when I was a "beginner" storyteller. I wanted to write a flat-arc/steadfast protagonist story, but I didn't know about those terms and I couldn't articulate what I was trying to do nor find resources to help me do it. I kept trying to apply change arc advice to a steadfast protagonist. It didn't work well and caused so many problems! Eventually, and unfortunately, I turned my steadfast protagonist into a change-arc protagonist in the process. Yikes.

While positive change arc protagonists are the most popular, they aren't the only type, and you don't have to write that type. So know what type you are writing and be discerning about what advice does and does not apply to it.

4. Character Agency Actually Makes the Character More Sympathetic

Let me admit something. While I think I'm somewhat of a natural at dissecting stories, I've learned I'm not a natural storyteller. After college, I could write pretty lines with a great style, but I really struggled with actual story elements. I don't think I'm natural at story. It seems I have had to learn everything the hard way in that regard. But I can't feel too bad about it, because trying to figure out why what I was doing didn't work has spurred much of this blog.

Anyway, when I started taking writing seriously, my protagonist did not exercise much agency. Bad things were just happening to him and he was just reacting, and he was really rather passive in plot (in part because I didn't understand the importance of goals nor that I could pick from three not just one type (see #1)). He wasn't making many choices or demonstrating his agency.

I wanted him to be really sympathetic because of his difficulties, and on a subconscious level, I thought that the lack of agency and control over his situation was doing that.

In reality, as counterintuitive as it sounds, the opposite is actually true.

Agency makes characters more sympathetic.

Here is an example I like to give when teaching others about this concept.

Imagine a story where a mother's daughter goes to the store and gets shot and killed by criminals.

It's sad, of course, but it seems random. Bad things happen to everyone.

Now, imagine a story where the mother didn't want to go to the store, and so chose to send her daughter instead. Then the daughter got shot and killed by criminals.

Most of us would say the second one is sadder.

Why?

Because the mom now holds some level of responsibility and accountability for what happened. If the mom hadn't sent her daughter, she wouldn't be dead.

Now, don't get me wrong, obviously the criminals are the real ones to blame, and the daughter also exercised agency by deciding to help out her mom (which makes the daughter a more sympathetic character too--she was just trying to help).

But in the second scenario, there is a stronger sense of cause and effect, where the mother's choices led to negative consequences.

And now, she may be haunted by the choice she made. What if she had chosen differently? Maybe she should have gone to the store herself. Or maybe she should have just used a delivery service. Or maybe . . . (I think you get the point).

This makes her more sympathetic. Not less.

And one way to make a character particularly sympathetic is to have her make choices with the best intentions and then have them lead to painful, costly consequences.

I could do a whole article on character agency in the future . . . or maybe I'll just save it for my online course. 😉

For now, this should give you a little something to think about regarding it: exercising agency makes characters more sympathetic, not less.

5. The Antagonistic Force isn't Only the Main "Big Baddie"--Your Story Should be Loaded with Them

In the writing community, we often talk about THE Antagonistic Force ™ in a story. We get very focused on THE MAIN Antagonistic Force ™--which makes total sense, I mean, duh! It's the biggest opposition.

But I sometimes feel like this leads to limiting perspectives that hurt our stories. (It certainly did for me and mine when I was learning.)

In reality, an antagonistic force isn't just some scary entity. An antagonistic force is anything that opposes the goal (see #1). It is the obstacles and resistance in the way of the goal. It's not something that is just heckling or annoying the protagonist. It's blocking, resisting, or pushing the character away from the goal.

And if (nearly) every scene should have a goal and should follow basic story structure, naturally that means there should be lots and lots and lots of antagonistic forces in a story--even if that particular antagonist only lasts for one single scene. Even if that antagonist isn't THE Antagonistic Force ™.

We need antagonists to have conflict (or even just tension--there is a difference) and meaningful consequences in our stories. That means an ally may step into the role of an antagonist if only for a moment, even if the ally isn't what we think of as a "baddie." (It may just be she has a different idea of what to do next, and that opposes the protagonist's current goal.)

And the antagonistic force isn't always "bad." It's simply something that opposes the goal. That's it.

So even if you have a main antagonistic force, make sure your story has lots of lesser antagonistic forces along the way--things that oppose the current goal. They may be temporary antagonists, but they are antagonists nonetheless.

6. Create Side Characters with Lead Characters in Mind

Once upon a time I brainstormed and ironed out a whole character who I, of course, thought was great. But when he finally got on the page with one of my main characters, the scene was terrible. The two did not go together well at all. It was some of the flattest most boring character interactions I'd ever written.

You see, while I liked both characters and worked a lot on each, they did not work well together--or perhaps, rather the problem was, they worked "too well" together, which was why it was so flat and boring. My main character in the scene was pretty nonchalant. The new side character I inserted was relaxed and lazy. Ack! What was I thinking? Because I had created each of them individually and because there were so many other features to them, I didn't realize how terrible they would be on the page alone together.

Rather than create each character as an "island," it's better to create supporting characters with the leads in mind. What kinds of qualities and attitudes are going to challenge and test your lead characters? What does your lead need to learn from this person? Or, what can the lead teach this person? What kind of person will uncover a new side to your lead? These are useful questions to ask when creating side characters.

In my story, in addition to being nonchalant, the main character valued honesty so much that he was often blunt (read: borderline rude). So I made the supporting character someone uptight who valued politeness. It took much less work on my part and the scene was much better for it.

7. Pretty Lines and a Nice Style Will Only Get You So Far (Which is Not Very Far at All)

As I already mentioned, when I got out of college, I could write in pretty lines and I had a nice style. In fact, style was one of the things I'd often get complimented on. But guess what? That doesn't matter if your story stinks.

There was an adage I would hear floating in writing communities around this time. Its basic idea was that if your lines are good enough, it doesn't matter what the story is, the reader will keep reading.

Today, I think this is a dangerous thing to be telling people, and when my story wasn't working out, I'd sometimes get stuck on that idea, thinking, Well, I have a good style, and if I just write this clever enough, witty enough, interesting enough, beautiful enough--X enough--the reader will keep reading!

Let's just say I wasted a lot of time doing that.

It didn't matter how beautiful or funny the lines were if the plot, characters, and structure were broken.

And ironically, I've learned that, actually, if you can figure out the story first, the lines will often come more easily. (This is because you aren't trying to make a pigsty look like the Taj Mahal. 😉)

Well, there you have it. And yet . . .

. . . with all that said, I also recognize I was not ready to learn and understand all these things when I did start writing seriously. And some things you can only truly learn and understand by diving into the craft. I mean, if you wait to know everything to start writing, you will be waiting forever!

But what about you? Is there anything you wish you'd known as a beginning writer? Let us know in the comments.

As always, amazing advice! I especially loved the reminders about forces of antagonism not having to be the big bad, agency making characters more sympathetic, and crafting side characters around the main. Thanks for this!

ReplyDeleteHey Josh, so glad it was helpful to you! Yes, those are all things I think writers easily forget . . . or just don't know . . . or haven't really thought of. Thanks for commenting 😊

DeleteThat's very helpful, in my case. Thanks

ReplyDeleteYou're welcome! :)

DeleteOne of the best articles on writing craft I've read in a while. I'll be keeping this one handy for reference. Thank you!

ReplyDeleteWow, thank you, Lori! I'm so glad it resonated with you.

Delete