Last time I shared seven things I wish I'd known as a beginning writer. Unsurprisingly, that wasn't an exhaustive list, and I've been thinking about it some more. So, I present to you, seven more things I wish I'd known as a beginning writer. . . .

1. The Central Relationship Needs an Arc and an Actual Plot

Many of us have been told we need a relationship plotline in our stories, but few of us have received any guidance on how to actually do that (unless, of course, you are writing romance).

And in my first novel attempt, back in the day, the central relationship was not romantic. I had an idea for what the relationship was like, but partway through the story, it wasn't working. And it was becoming super annoying.

What I didn't realize was that it was annoying because it was mostly static. Nothing was changing. The characters weren't growing closer together or further apart. Instead of the relationship plotline having "peaks" and "valleys," it was mostly just a straight line.

Of course, I knew it was going to change at the end.

But what I didn't understand was that it still needed a plot through the middle. 🤦♀️ Which means it still needed the basics of plot: goal, antagonist, conflict, consequences.

Not just interesting interactions and conversations. Not just banter and pastimes.

In my last post, I mentioned the three basic types of goals: obtain, avoid, maintain.

Well, in relationship plots, this translates into these three basic goals: grow closer to the person (obtain), push further away from the person (avoid), maintain the relationship as is (maintain).

The antagonistic force is whatever gets in the way of that. If your protagonist wants to draw closer to this person, then an antagonistic force should be pushing him away. If he wants to be apart from this person, then the antagonistic force should be pushing him closer. If he wants to maintain the relationship as is, then the antagonistic force is what disrupts that. This creates conflicts and should lead to consequences.

If you have a relationship plotline, it needs an actual plot.

2. Choose a Tentative Theme Early, to Better Shape and Evaluate Your Story

If you've been following me for a while, you probably know I consider these three things to be the triarchy (formerly known as "trinity") of storytelling: character, plot, and theme.

Each of these elements comes out of and influences the others.

This also means you can use each of these to help shape and evaluate the quality of the others.

It's much easier to write a solid story when you understand all three.

If you have only one or two pieces, it's harder to discern which ideas are just okay and which ideas are great. It's harder to discern what does or does not belong in your story.

The best ideas for your story are going to come from and touch each of those three things.

Most beginners are familiar with concepts of characters and plot.

Few know anything about theme.

And fewer still have the desire to learn anything about theme. It's often seen as unimportant or something that "just happens." Okay, sure, it could just happen. Maybe.

But writing your story will (in the long run) be much easier if you at least understand some basics about theme.

I have so much to say on theme, it could probably fill up a book (and maybe someday it will), but for now, if you want more information on it . . . I'd recommend starting with this article: The Secret Ingredients for Writing Theme. It breaks down the key elements of theme, which can give you a good foundation.

Even if your theme ends up changing a bit, starting with an idea in mind will help keep your story on track.

3. Your Story Needs a Counterargument

Remember when I was talking about theme, and implied I wasn't going to go into it that much more? Well . . . I guess I'm going to go into it a little more.

The thematic statement is the argument the story is making about life.

But it's not really an argument if no one is disagreeing.

This means your story needs a counterargument (I call this the "anti-theme").

This counterargument will often manifest within the protagonist (as a "flaw" or misbelief or something the character needs to cast off or overcome) and/or within the main antagonistic force.

It can technically show up in other places and in other ways, but let's keep this basic.

So if your story ultimately shows the audience that it's best to be merciful, then a counterargument for that could be that it's best to enforce justice (Les Mis).

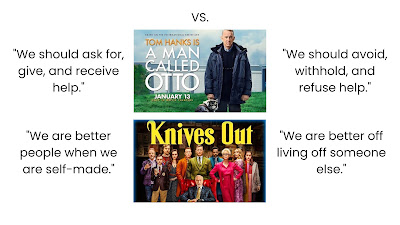

If your story ultimately shows the audience that it's best to ask for, give, and receive help, then a counterargument for that could be that it's best to avoid, withhold, and refuse help and do everything yourself (A Man Called Otto).

If your story ultimately shows the audience that it's best to rely on faith, then a counterargument for that could be that it's best to rely on technology (Star Wars IV: A New Hope).

The two arguments are locked in a "battle" of sorts, similar to how the protagonist and antagonist are, because they are in opposition to one another (see #5 in previous article).

The arguments need to be "shown" more than "told." And the counterargument should be given fair weight, because doing so will actually make the whole theme (and plot and characters) stronger.

Here are some examples to think about:

4. Writing More isn't Enough to Take Your Work to a Professional Level

We are often told that if we want to be great writers, we need to write more. And this is true. To an extent.

I've worked with writers who had been writing for decades, but were still at a beginner level.

I have known writers who bent over backward to meet word count goals, only to end up with a pile of slush they couldn't see their way out of.

I myself have spent enormous amounts of time and words trying to write something brilliant.

But for the vast majority of people, putting in the time and word count isn't enough.

What is the point of clocking in more and more hours and typing more and more words if you don't know how professional-level stories actually work?

Don't get me wrong--you absolutely need to put in time and words, and they absolutely will help you improve! And yes, quantity can improve quality.

But also remember this: You don't know what you don't know.

And if you are practicing imperfectly, that doesn't guarantee that one day it's going to be perfect.

If I have lousy technique every time I go bowling (and frankly, I do), that doesn't guarantee I'm going to get any better if I don't know what I'm doing wrong or how to improve or what good technique looks like--no matter how much time I put in.

This is sadly usually true for writing.

I'm not saying that no one gets to the professional level by only clocking in writing hours, but just that . . . I don't think most of us do. And I think some of us could spend decades clocking in the hours, and really, just be spinning our hamster wheels because we don't know what we don't know--we don't know why professional stories are professional level, so we don't know how to improve.

Hands-on practice is vital.

But so is education.

Sometimes it's actually more beneficial to learn about the craft from someone than to complete your Xth writing sprint to meet your word count goal.

If I could speak to my past self, I would tell beginner me to spend more time studying the craft. In the long run, it would have actually helped me get better easier and much faster than clocking in another hour of writing (that would have ended up in the garbage bin anyway). I've put in a lot of hours that didn't get me very far because I didn't fully understand where I was trying to get, or how.

There is always more you can learn. And especially in the writing world, there is always another perspective to learn what you think you already know. Many writers talk about the same subjects, but come at them from different angles, and learning even those different angles can help you refine your understanding of that subject.

I'm not going to say that tomorrow you have to sign up to take a bunch of courses (though you can if you want), but make time to learn about the craft regularly. You may want to ask yourself: Is it better for me right now to write for an hour or to learn for an hour?

5. Conflict for the Sake of Conflict is Actually Filler--You Need Consequences!

There is an adage in the writing community, which is that story = conflict.

And once again, it's true. To an extent.

But adding a bunch of conflict isn't enough to make a story good.

If the conflict doesn't change anything--if it doesn't have at least the power to change any outcomes, then what is the point? It's just stuff happening.

Who cares if a bomb is going to go off, if no one or nothing significant is in danger of being blown up?

Conflicts need consequences to be meaningful.

It's really the consequences that hook and draw readers into the story. Or at least, the potential consequences. It's potential consequences that make up the stakes in the story.

And they draw the audience in because the audience wants to see if what could happen actually does happen.

Once the audience understands the potential consequences (the stakes), they care about the conflict, because how the conflict is resolved will affect what happens next. The conflict now has significance because it changes the direction of the story, it changes the future.

Consequences also improve the story by strengthening a sense of cause and effect.

As I touched on in my previous post (see #4), random bad things happening is actually less effective (and makes characters less sympathetic). And random good things happening is also less effective (and makes characters less admirable). Instead, it's better if the bad and good things that happen come as a consequence to how a conflict was resolved.

This often happens even at a scene level. Just as nearly every scene should have a goal and antagonist, nearly every scene should have conflict. How that conflict is resolved in that scene should also carry consequences and affect what's going to be happening in the near future of the story (generally speaking).

Consequences also allow the audience to experience tension, which, as counterintuitive as it sounds, can be more effective than outright conflict. Tension is the potential for problems to happen. Conflict is actual problems happening. Tension makes the audience feel suspense. But suspense often only exists because the audience understands the potential consequences (the stakes) in play.

If there are no known consequences, then the conflict often doesn't really matter to the audience, because they can't see how it will change anything significantly.

6. Starting in Medias Res is Actually Harder, not Easier

A lot of beginning writers struggle with beginnings--which makes sense, because they can be very difficult to write.

And so a lot of beginning writers are told to open their stories in medias res, which translates to "in the midst of things." This basically means you open the story up with some form of rising action (conflict)--usually it's that scene's rising action (see #2 in my previous post).

In other words, you are essentially cutting off the scene's setup.

While this can be effective, and while I may be unpopular in my opinion, I don't feel that it makes things easier. In fact, more often than not, I think it's actually harder to start in medias res.

This relates to what we just talked about above in #5.

When we start a scene in medias res, we are starting with conflict, but if the audience doesn't know why the conflict matters, then it won't hold them for very long.

When you cut off the setup of a scene, you now have to find a way to convey who is there, where is "there," what is there, when, and why we care (the why is the stakes).

--all without slowing the pacing.

This is why I think it's often (though not always) more difficult.

Now don't misunderstand me. I'm not saying you can't start in medias res, or that you shouldn't start in medias res.

I'm just saying it's tricky.

Instead, I would personally recommend starting just before the scene's conflict. Start early enough to give the audience context to understand what is about to go down: where and when the scene takes place, who is there, what the goal is, and what the potential consequences are. Make the setup long enough to convey the important stuff, but short enough to stay interesting.

Then get to the scene's conflict, the rising action.

You can read more than you probably want to know about in medias res here.

7. Yes, You Really Need to Do That If You Want to Write at a Professional Level

This last thing is pretty nonspecific, as it's not about one particular piece of writing advice. When I started taking writing seriously and going to conferences and listening to podcasts and what have you, I often felt skeptical of what I heard. Now, sometimes that skepticism served me well (and has led to many of my blog posts), but other times that skepticism held me back. What's the difference?

Being skeptical of "writing rules" has, in the long (long) run, served me well, because it has actually led me to better understand the rules, why they are rules, how they work, and how and when to break them.

But sometimes it wasn't that I was skeptical of the rule itself. It was that I was skeptical that I needed to do X at all. I was skeptical that professionals actually did X.

For example, I would hear about Swain's scene structure and think, Yeah, there is no way most people actually do all this and put all this thought into their scenes.

Or I would run into a breakdown of character arcs and think, Yeah, there is no way most people actually do all these things to write a great character arc.

And in the community, I have brushed up against this same mentality from others. Viewpoint is a popular subject. "Do I really need to be in one character's viewpoint at a time?" or "Is it really that big of a deal that I described the viewpoint character's face?"

And I'm like . . . on the one hand, no, and on the other hand, well yes--if you want to write at a professional level and be competing professionally.

Not that no professional ever varies from that, but just that those are exceptions that prove the point.

And it's not even that every professional is consciously doing X thing. They may be doing it subconsciously. But X thing usually still needs to be there, for the story to sound professional.

So yes, you really do need to do X thing if you want to be writing at a professional level.

If you don't care about writing at a professional level, then obviously you don't have to. It's totally valid to write for a hobby or just for fun.

Now I will echo what I said last time. If I had waited until I understood all these things to start writing, I would have been waiting forever. And some things I would have never properly understood without the actual writing process. Yes, we need to be educated on how stories work, but it's also important to sit down and write.

~

Seconding #4. It's important to pick a new skill on each project and practice it, as well as studying long-term writers and what they do well. But it's challenging to find resources for new skills after a certain level. Seems like everyone focuses on beginners....

ReplyDeleteTotally agree. To be honest, I stopped reading writing craft books and going to conferences for a few years because I felt like what I was getting was mostly for beginners . . . which was great when I was a beginner, but I wasn't anymore. There will always be more beginner writers than intermediate or advanced, because people drop off, which is fine, but that also means that people can usually make more money or reach a bigger audience by catering to beginners. It's hard to find resources for intermediate and advanced writers.

Delete