When it comes to writing stories, pacing really happens at three levels:

- in the overall story (the "narrative arc")

- in the scenes

- in the lines (passages and paragraphs)

Back in January, I taught an online class about pacing--a lot of you probably remember because I mentioned it a few times prior. Before, during, and after, I realized I had more to say on the topic than I could possibly fit into my thirty-minute session, so I thought I would do a few posts exploring it in more depth.

Often when people are talking about pacing, they are talking about it at a scene or line level, but the overall story has its own pacing too. Some sections will have faster, tighter, and more intense pacing, while other sections will have slower, looser, or more leisurely pacing.

It's also important to acknowledge that--especially when it comes to narrative arc--this is somewhat relative. What might be "fast pacing" in a drama, probably wouldn't be considered "fast pacing" in a thriller. To some degree, what's "fast" or "slow" relates to the pace the story sets up initially.

Nonetheless, any story of any genre can be in danger of speeding sections up too fast or slowing them down too much.

So let's dig into more about pacing within the narrative arc.

Pacing and Structure

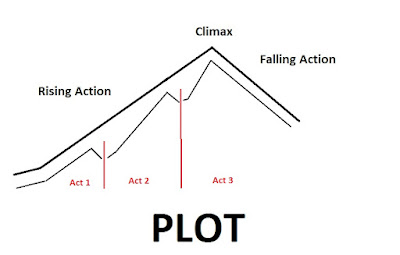

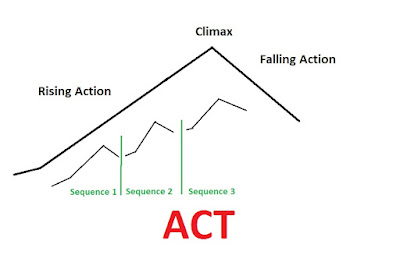

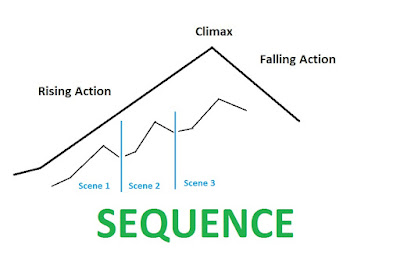

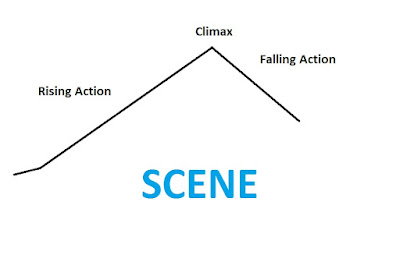

In the past, I've talked about how all structural segments really fit into this basic shape:

Whether it's a scene, sequence, act, or whole story. This shape is like a nesting doll or fractal--it fits smaller versions of itself inside:

This means that generally speaking, ideally, each of these structural units has its own climactic moment. This is also called a "turning point," because it turns the direction of the story.

The bigger the structural segment, the bigger the turning point--meaning an act's turning point is going to have more ramifications than a scene-level turning point.

This is a great way to start understanding structure.

Essentially, each of these units has:

- Opening/Setup

- Rising Action

- Climax

- Falling Action/Resolution

Typically, the pacing is going to get faster, tighter, or more intense the closer it gets to the climactic peak.

Afterward, it will get looser and slower with the falling action.

In some situations, the writer may cut off most, if not all, of the falling action, but generally speaking, the pacing is going to slow down into a "valley." And if you are working with a smaller unit than the whole plot, this shape then repeats itself, so you then hit the opening or setup of the next segment.

Ideally, each segment will open with a hook to grab the audience, but after that, the pacing may be a little calmer as we get to the setup and before it really hits the rising action, where the main conflicts happen and develop.

Again, remember this is somewhat relative. You can give yourself a good headache if you overthink or misunderstand how this works, mainly because smaller shapes repeat inside bigger shapes. The smaller shapes have the same parts, but are small scale (read: less intense).

Typically, the falling action of the segment is more reactionary. It's the character or characters reacting to the turning point. Because the turning point changed the direction of the story (and usually in an unexpected way), the character now needs to take that in, process it, and decide what to do next.

Think of this on the large scale. At the climactic peak of the narrative arc, the conflict with the antagonist comes to an end. The character (and the audience) needs a moment to process emotionally and mentally what just happened. Then the protagonist must decide what to do next. The falling action usually hints at a "new normal," or at least the next path the protagonist takes, whether that's happy-ever-after or preparing for the next adventure or something else.

Many think that pacing mainly comes from the word count, and certainly word count plays into pacing. But when it comes to the narrative arc or even within scenes, structure often has to do more with pacing. For example, we wouldn't necessarily want to "speed up" the climax of the whole story by making it extremely short. Making it only a few pages doesn't necessarily make it extra intense. Just as you wouldn't want to make the falling action way longer than the climax, thinking that will make it better. In almost all stories, the falling action will have fewer words than the climax. Technically, someone could sustain a fast pace of a segment for more pages than the slow part of the segment. It's not strictly tied to word count. However, it's possible to make a segment too fast or too slow through word count.

Basically:

Word count --(influences)--> Pacing

But not:

Word count = Pacing

Along with structure, hooks, tension, stakes, suspense, and conflict play critical roles in pacing. More of them make the pacing feel tighter, and less of them make the pacing feel looser. We hook the audience at the beginning to get them to stick around through the setup and the start of the rising action. The conflicts and stakes should get bigger as they develop and become more complicated--they escalate. This makes the pacing feel more intense. After the turning point, those things hit an outcome (for better or for worse) and the conflict ends (if only temporarily). Because it ended, the pacing gets calmer and slower--how calm and how slow often depends on what structural unit you are working with. Obviously, in the plot as a whole, it will be calmer and slower in THEE falling action, than it would be in a scene. Nonetheless, it still gets calmer and slower compared to the climax, regardless of what unit you are working with.

When looking at the narrative arc as a whole, it's obvious how these things apply. We want the climax to be fast and intense, and if we handle plotting and structure right, this will happen naturally to some degree, because all the conflicts will be hitting their high points around that time. When they are resolved, it slows down and we tie up the story.

And in the beginning of the story, we must work to hook the audience so they'll want to stick around long enough to get to the main conflict.

But what about everything else in between?

This is when it's helpful to go down to the next structural unit: acts.

An act follows the same shape. This means that the beginning, middle, and end will each get a big climactic turning point.

So what are these big moments?

In Act I, this will be what's called "Plot Point 1," "Crossing the Threshold," or "Break into Two," depending on what structure you use (7 Point Story Structure, The Hero's Journey, and Save the Cat! respectively. They all have different names for essentially the same moment.).

We open Act I with a hook, which will hopefully also be big enough to be THEE hook for the whole narrative arc. We spend time with setup: Who is this story about? Where does it take place? When does it take place? And we also establish a sense of normalcy.

Then the inciting incident hits (this is also called the "Call to Adventure" and the "Catalyst," depending upon your structural preference), which kicks off the story, both for the narrative arc as a whole and for Act I. This is something that disrupts the established normal, and it can either be a problem or an opportunity for the protagonist.

This arguably starts the rising action, in the whole narrative arc, and especially in Act I.

(While it is possible for Act I to have its own separate "inciting incident" for an act-level problem or opportunity, let's keep this simple for now. I might do more posts specifically on acts in the future. But, if you feel you have multiple "inciting incidents," that might be part of what's happening.)

The protagonist is now having to deal with this problem or opportunity and what to do about it.

On the act level, this comes to a head at Plot Point 1(/Crossing the Threshold/Break into Two), where the protagonist chooses to accept the opportunity or chooses to try to address the problem, and engages with the main conflict. Often this is marked with a big moment--such as a parental figure dying (like in Star Wars) or discovering your birth dad is in New York City and on the naughty list (like in Elf). Whatever it is, it's essentially a moment that helps push the protagonist through a Door of No Return.

What follows is usually a transitional segment where the protagonist "journeys" (literally or figuratively) to a new "world" (literally or figuratively). Both Luke and Buddy literally travel to a new place, but in many stories, this may be seen to be more of a new state of being (such as a character taking on an old lady persona as in Mrs. Doubtfire). The character gains a new goal as they accept the "adventure."

Know that I'm simplifying this a bit, as this is meant to be a post more about pacing than about structure.

But that big moment and decision to engage with the main conflict is the climactic moment of Act I, and what follows is often the character reacting to that moment.

This means the pacing gets tighter at that moment, and a bit slower after that moment.

The climactic moment of Act II, is Plot Point 2, which is also known as "The Ordeal" or "All is Lost." This is usually a part in the story where the protagonist engages with the main conflict, which leads to a loss or "death" (literally or figuratively). This is the biggest engagement with the main conflict so far. Meaning, it's bigger than the high point of Act I, and bigger than anything that came in the middle. So the pacing gets tighter and more intense here.

It's also followed by the biggest lull of the story--Plot Point 2's falling action. Usually, the protagonist fails or loses or "dies" from this engagement and falls into a "Dark Night of the Soul" moment. (Alternatively, the protagonist may succeed in the external conflict, but something isn't right, something is missing or wrong--it's a hollow victory, and this also leads to a lull.)

This is also followed by a transitional segment that takes us into Act III, when the protagonist gains something (whether plot-driven or theme-driven) that enables him to head toward THEE climax. This gives him a new act-level goal for the ending.

Finally, the climax of Act III is also simultaneously THEE climax, and same goes for the falling action.

When you have structure handled, pacing will often come with it--at least to an extent. But looking at the story this way, you can see where you want the pacing to be faster, more intense, and tighter, as well as when you probably want it slower, calmer, and looser.

There are just two variations I want to mention in regards to acts . . .

Often in the writing community, we refer to stories as having three acts: beginning (Act I), middle (Act II), end (Act III), and I try to (more or less) talk about story in this way, just to keep confusion to a minimum.

But personally, I feel acts have more to do with this structural shape than they have to do with beginnings, middles, and endings.

Another key moment in the narrative arc is the midpoint, which happens at the middle. This is often where the protagonist gains a bigger understanding of what's really going on with the antagonist and the main conflict, which then enables them to become more proactive in addressing the problem (they sort of go into "attack mode"). This is also often marked by a big event--either a victory or a failure (or at least a seeming victory or a seeming failure).

In stories that have big midpoints, I actually think it's helpful to think of them as having four acts:

This means the pacing will be tight and intense at the climactic moment that comes at the midpoint.

After the high point, there is usually a bit of a lull as the protagonist processes and decides what to do with the new insight they've gained. This also may have a bit of a transitional segment that leads to a new goal about how to go on the attack for the second part of the middle.

Don't forget, though, that sometimes the falling action gets shortened or cut off or may simply not be on the page. And again, this is a post intended to be more about pacing than structure, so I'm trying not to get too detailed.

The other variation that sometimes happens is that the highest climactic peak of some stories actually hits at Plot Point 2 (The Ordeal or All is Lost moment), with the whole ending showing how the protagonist then applies what he learned from that experience to resolve the remaining conflict and wrap the story up (the film Old is an example of this).

For what it's worth, I actually picture these stories as having only two acts, since there are only two really high points:

In any case, understanding act structure will help you see where you will naturally want intensity and where you will naturally want lulls.

Long ago, I used to get confused when I felt like I needed to have a lully scene, worried that it was boring or would kill the pacing. I didn't understand that on the narrative level, the story should have lully scenes. I didn't understand that pacing happened on such a large level.

Lully scenes are important in giving not only the protagonist a chance to process and react to what's going on, but also the audience. If there are no lulls, there is no time to digest what just happened. We don't get to react to what just happened. Or wonder about what to do next. We don't have a chance to catch our breath or let our worry fester or our hope build.

It can shortchange a lot of emotional breadth.

Then again, how much time and space you spend on the lulls may be determined by the kind of story you are telling. In a thriller, you will probably want to keep the lulls shorter than average. If you are writing literary fiction, you may want to draw out the lulls longer.

It all gets down to your story and the effect you want on the audience.

If you are having problems with overall narrative pacing, check act structure.

Pacing and Proportions

Also long ago, I used to hate when instructors talked about percentages. Statements like "X needs to happen at 25% into the story" felt so stifling to creativity!

. . . but after wandering around the pits of Writing H-e-double-hockey-sticks, I started to think that maybe . . . there was something to all that percentage junk . . . 😕

Well, present-me is here to tell you, there is!

However, that doesn't mean there isn't wiggle room or times to break the rules; it's just that, like with anything in writing, you need to know what you are doing first.

Like it or not, we humans are subconsciously conditioned to expect big moments (*cough cough* major turning points *cough cough*) to happen at certain places in a story.

I would even argue that it goes deeper than conditioning. For one, if there aren't big turning points at the right places, it's more likely that what is currently happening in the story is going to start feeling repetitious. Like, imagine if Harry Potter spent an even bigger part of the story trying to get his Hogwarts letter. How long can you really play around with that conflict before it gets boring? Before the audience is aching for some kind of change or progress? The big turning point ("Yer a wizard, Harry") is the change and progress. And if it takes until 40% into the story to get to that turning point, you can bet your bottom dollar that the audience has already bailed or is snoring. A conflict about trying to get a letter that doesn't really change, isn't sustainable.

I would also argue that turning points are archetypal and even a reflection of how our human minds work. We go along our lives until--bam--a problem or opportunity disrupts us. We wonder about what to do, debate about what to do, maybe resist what we should do, until we eventually come to a decision about it. Or, we take on goals, and as we try to pursue them, we face obstacles, and when it doesn't turn out in our favor, we react and try to decide what to do next, then we make a new plan and come up with a new goal. We don't sit there and react to it for the rest of our lives (or if we do, we need to get some therapy to move past it).

In any case, in the narrative arc, problems with pacing can arise if it takes too long to get to certain turning points (nothing kills pacing quite like repetition and stagnation). Or, if you get to them too quickly, which means there wasn't proper escalation or build-up (rising action).

Percentages are helpful as guidelines.

And here are a few to go with our acts.

- Plot Point 1 should happen around 25% into the story.

- The midpoint should happen around 50% into the story.

- Plot Point 2 should happen around 75% into the story.

As always, you can find examples of variations.

But having this as a baseline gives us the capacity to talk about timing as well as variations.

Generally speaking, if your story doesn't get close to this, it's disproportional.

If the midpoint doesn't happen until 62% in, then it takes too long for the protagonist to become more proactive and go on the attack. This likely means the section before this is becoming repetitious and stagnant. Likewise, we now don't have as much time to properly build up to the climactic moment of Plot Point 2, for best impact.

If Plot Point 1 is hitting at 31%, the setup is probably taking too long and getting boring.

Again, these are just general guidelines--I'm not saying no story can't ever play around with these any time or anywhere.

For example, some stories start in narrative in medias res, which can change this approach. Some rare stories are structured so that the beginning, middle, and end are all the same length, which definitely changes the percentages.

But if you are having pacing problems at the narrative level, consider looking at the percentages and checking the proportions.

Pacing in the Document

Outside of structure and percentages, there are a few other ways to affect pacing at the narrative level. And this has to do with how the story is actually presented to the audience.

Chapter lengths can influence how fast or how slow the audience feels the story is going. Short chapters make the audience feel like they are tearing through the book faster. Long chapter makes it feel "meatier."

This sort of thing can also happen with viewpoint characters. When working with multiple viewpoint characters, some writers will shift between them quicker near the climax of the story. This makes the moment feel tighter, more intense, and more dramatic--assuming, of course, all the viewpoint characters are active participants in the climax. (And it should be mentioned, you can also use this effect at other climactic moments, like within acts).

When it comes to printing, you can also use page and font size in similar ways you use chapter lengths. Reading a "chapter book" feels much faster, not only because the book itself is shorter, but because there are fewer words on a page and it has bigger font. My Lord of the Rings omnibus, on the other hand, has tiny font on big, thin, pages.

Depending on how you plan to publish your book, that may or may not be relevant to you, but I wanted to mention it nonetheless.

Whew! That's about it for pacing on the narrative level. Next time, I'll talk about pacing on the scene level, then follow up with the line level (which is probably what most people think about when it comes to pacing).

Happy writing!

Read What Others have Written on Pacing

Pacing in Writing by Reedsy

What is Pacing in Writing? by Now Novel

How to Master Pacing by Master Class

0 comments:

Post a Comment

I love comments :)