You can find a lot of information on story structure in the writing community, but when it comes to discussing variations on structure . . . that gets harder to find. I've been talking a lot about story structure on here, particularly over the last two years. And every so often I feel like I need to "cleanse" myself of all the rules, percentages, and beats, and remind everyone that writing doesn't need to be an exact science. Not every successful story fits story structure perfectly.

With that said, like all writing "rules," once you understand structure, it's easier to "break" it successfully. The rules are really more like guidelines.

Story structure exists to help us understand and write great stories. It's not necessarily there to use as a rubric to decide whether a story is good or bad. Sure, it can be used as a sort of checklist to help us evaluate our own stories, or to help us dissect other stories, but it's not necessarily a rubric to determine what "grade" the story gets. If a story is successful, we can use structure to help us understand why that might be so. But if a story is successful, we don't use structure to give it a "bad grade" just because it didn't fulfill everything in the exact, "right" way. If it's successful, it's successful. I don't think anyone is saying Wonder Woman is unsuccessful just because it had some variation.

If everyone followed the "perfect" story structure, exactly, all the time, things could potentially become annoying--especially in the wrong hands.

So lately I've been on the lookout for popular and/or successful stories that have structural variations. Remember that most successful stories do have mostly the same pieces--they just might be rearranged a different way (a.k.a. a variation). I'm sharing some of what I've found today. This won't be comprehensive, as there are probably more variations than I could fit in a blog post, but it will teach you about some of them, and maybe give you some ideas on how to use them.

With Structural Segments & Beats:

"The middle makes up about 50% of the story."

Variation Explanation: Some stories are structured so that the beginning, middle, and end are three equal parts. Often the middle is the longest segment, but not always. For an example of this, pick up any of The Hunger Games books (even the prequel)--Suzanne Collins writes all of these books in three equal-sized acts. Years ago, this used to confuse the dickens out of me when I tried to dissect them while studying structure. I could not, for the life of me, figure out how she was handling structure. Sure, it's blatantly sectioned into three parts with dividers, but I was so confused when mapping out the beats with their percentages, because it didn't fit what I was taught. Finally, I ran into the concept of some stories having three equal-sized acts, and alas--my mapping worked! (Right along with the dividers 🤦♀️.) All of her middle beats happen in half the amount of space. All the structural beats are there, just crammed together in the middle, compared to most stories.

(Worth noting is that the films take the same events but structure them differently. The books are structured as three equal-sized acts, but the movies aren't.)

"This moment happens X% into the story."

Variation Explanation: Percentages can be really helpful as guidelines. I mean, you wouldn't want the inciting incident to happen 40% into the story--it would make the setup drag, and the reader would probably be bored witless by that point. The audience is conditioned to expect significant turns to happen around certain times, and if they don't, something might feel off to them.

But of course, sometimes varying the timing totally works. In Wonder Woman, the midpoint, which usually comes right at the 50% mark, hits at 43 - 44%. This makes the later beats slightly longer. Did anyone feel windswept because the first "half" of the story was actually less than a half? Probably not. They were just enjoying the film.

However, if they did feel windswept, then we'd want to revisit and rework the story structure, so it's more pleasing.

"After the inciting incident, the protagonist hesitates about what to do."

Variation Explanation: Placed in the beginning of the story, the inciting incident is usually either an opportunity or a problem that disrupts the protagonist's established normal--it's the first domino that kicks off the main plot. In The Hero's Journey structure, there is a moment after the inciting incident where the protagonist refuses the opportunity or ignores the problem. In Save the Cat! structure, this is seen as a "debate"--the protagonist debates about what to do. Basically, this is a moment where the protagonist hesitates.

But not all protagonists actually hesitate. Many protagonists don't, like Diana in Wonder Woman, Ashitaka in Princess Mononoke, and Marlin in Finding Nemo.

The purpose of this moment is to impress upon the audience the seriousness of the opportunity or problem--if the protagonist goes on this journey, he may not come back the same. The purpose of this moment is to impress upon the audience the stakes--what the character is at risk to lose (and maybe gain).

Often if the protagonist doesn't voice hesitancy here, another character will instead. In Wonder Woman, the Amazons refuse to help humankind, and Diana's mother tells her not to leave while warning her of the stakes. And in Princess Mononoke, the elders speak out against Ashitaka departing their village. The same pieces are there, but rearranged.

Sometimes the hesitancy won't be voiced at all. In Finding Nemo, Marlin immediately reacts to Nemo being taken, with no one nearby to warn him or voice the stakes.

For more about how, when, or why the protagonist hesitates (or doesn't hesitate), check out The Structure of Story by Ross Hartmann.

"The protagonist becomes more proactive against the antagonistic force(s) after the midpoint."

Variation Explanation: This is probably almost always true--and for good reason. Usually after the midpoint, the protagonist has a better understanding of the antagonistic force and what to do to try to defeat it. This propels her to take stronger, bigger, more assertive actions than before.

But if you are working with a positive steadfast protagonist who begins to entertain the anti-theme, the lie, at the midpoint, then you'll probably be showing how the protagonist isn't addressing the antagonist. This is exactly what happens in Sam Raimi's Spider-man 2. At the midpoint, Peter decides he doesn't need to be Spider-man, he doesn't need to be responsible. So he spends the second half of the middle doing the opposite of what he should do. He spends it ignoring the antagonistic forces. As a result, crime goes up. Similarly, in The Lion King, Simba stops believing he's destined to be the true king at the midpoint (when Scar kills Mufasa), and spends the second half of the middle turning his back on his destiny, eating bugs, and being lazy--the exact opposite of what a lion king should do. As a result, the Pride Lands become desolate under Scar's rule.

It should be noted that if you are working with a negative steadfast protagonist who begins to entertain the theme, the truth, at the midpoint, this will be similar, yet reversed. The protagonist will begin acting on what is right or correct, and things will seem to be going better. Since this scenario is reversed, the antagonist likely embodies the thematic truth, so the protagonist is no longer being proactive against them in here either. (And some of you who have no idea what a negative steadfast protagonist is, are probably scratching your heads.)

Outside of these two types of protagonists, I have a hard time thinking of when this variation would work well. But nonetheless, it is a variation that works.

"The middle ends in failure, followed by a 'Dark Night of the Soul' moment."

Variation Explanation: Usually at the end of the middle, the protagonist faces his biggest challenge yet (this is sometimes called "The Ordeal" or "All is Lost" moment), and it ends in failure. The protagonist failed to defeat the foe (whether that's internal or external), usually because he has something he still needs to learn. It may be that someone helped him get out of the dire situation, but he's still a failure, because he couldn't be victorious. This leads to a lull often called the "Dark Night of the Soul." (And in some stories this is all more pronounced than in others. In others, it can be pretty subtle.)

But not all middles end in failure. Sometimes the failure is swapped out for what's called a "hollow victory"--the protagonist succeeds, but it doesn't feel like a victory. There is something missing. There is something not right. The protagonist got what she wanted, but she still hasn't overcome her flaw or learned what she needed to on this journey.

In Zootopia, Judy wants to be a renowned bunny cop, but when she’s finally recognized as one at the end of the middle, it feels hollow because she hasn’t yet addressed her personal flaw. Inside, she knows she’s not a good cop, because her investigation actually made the world worse by increasing prejudice, not remedying it. This is a hollow victory.

Even with a hollow victory, a lull still typically follows. But rather a lull based on defeat, it's a lull based on "something is missing." Something is "incomplete" (And again, in some stories this is all more pronounced than in others.)

"The antagonistic force is always strongest at the end--this is where the story hits its highest peak."

Variation Explanation: Most stories will hit their high point at the end, when the protagonist and antagonist go head to head for the last time. But in some stories, the high point will be The Ordeal or All is Lost moment. This leads to the lull, and then a final turn where the protagonist learns something valuable (that something can be theme-driven or plot-driven) that takes them into the story's end--which is simply made up of the protagonist applying what was learned to set the world right (at least "right" to them).

For what it's worth, I personally view these stories as being two-act stories, as there are really only two high points.

VS.

But if that just makes you more confused, feel free to ignore that.

I saw a recent example of this in M. Night Shyamalan's Old. Without being too spoilery, in case anyone still wants to see it, I'll describe the structure. The premise is that a bunch of people are stuck on a beach that makes them age extremely fast--a half hour is equivalent to a year. At the end of the middle, we have a climactic peak, The Ordeal, followed by a sad lull. Then the--ahem--remaining characters try to decide what they are going to do. Do they keep trying to get off the beach (every attempt has been largely unsuccessful, not to mention dangerous)? First, they decide to take a break and build sandcastles. In a story where you age a year per half hour, that probably sounds weird, but it's thematic. In a story that revolves around the concept of time, only when the characters decide to enjoy the present, are they able to come up with a solution to their predicament. One character recalls a clue that leads them to a potential escape. So the final turn is both thematic (enjoy the present) and plot-driven (recall the final clue).

The remaining characters work to execute their plan. There isn't another climactic moment, a peak, after that. There is still an end segment, and there are still antagonistic forces, but they are dealt with rather easily and quickly. The end is about learning what's really going on and then applying that knowledge to set the world right. There isn't another nail-biting moment.

Another example of what I would consider a two-act story, is The Greatest Showman. There are only two main climactic peaks--when P. T. Barnum gets the idea for the circus and when he returns home early from his tour with Jenny Lind. The rest is about figuring out what's really going on (which is thematic) and applying it to set things right.

With Plot Elements:

"Everything must move the story forward. Every scene must create a significant change."

Variation Explanation: I often talk about how everything in a story should move forward the plot, character (arc), or theme. This is generally true, but it's not always true. Another important feature is setting. And while I would argue that most scenes need to do more than just further the setting (why not further the plot and the setting in the same scene, for example?), in some stories that are largely about the setting, simply furthering the setting works fine. Sometimes in a fantastic new world, we just want to enjoy the worldbuilding. Or maybe it's a rich historical setting we've dreamed of visiting. Maybe all we want from a scene is to de-gnome the Weasleys' garden. Alternatively, some scenes are just there for fun--maybe to give us a laugh. Ideally, I think it'd be great to tie these scenes at least to theme, but that doesn't always happen. (Though the question I often ask is, wouldn't it be better if it were at least tied to theme?)

Some scenes don't further the story or have significant change because the point is to show how things don't progress and don't change. I recently rewatched Harry Potter and the Half-blood Prince, and there is a segment where Harry is trying to get a memory from Slughorn and repeatedly failing. It doesn't really further the plot, the character arc, or the theme. The point is to show that there isn't progress, that there isn't change. This shows the audience the difficulty of the task. Totally acceptable. Though I will admit that usually in such situations, this is best rendered as summary, rather than scene.

"Everything in the end must have been at least foreshadowed before."

Variation Explanation: This is a great guideline to live by. Definitely try to do this. We usually don't want to solve the main conflict with a deus ex machina. With that said, some successful stories have whipped out something new at the end--something that seemed to come out of seemingly nowhere.

In his online class lectures, Brandon Sanderson talks about how he ended up doing this sort of thing in the first volume of Mistborn, where Vin is able to somehow use the mists against the antagonist. It was a part of the magic system he was going to introduce later in the series, but when his editor said he thought the ending needed a little more oomph, Sanderson pulled it into the climax to be explained later. But it wasn't really foreshadowed.

Similarly, in the first Harry Potter, Harry magically defeats Quirrel by burning him with his own hands. That ability or type of magic wasn't really foreshadowed anywhere.

Sure, one may argue that the mists are important earlier in Mistborn, and Harry learns of his mother's sacrifice earlier in the story as well, but the abilities weren't foreshadowed. They are explained later though.

Both series went on to be best-sellers.

But would the books have been better if these abilities were properly foreshadowed ahead of time? Probably. But I don't think any of us would say they are bad stories because the foreshadowing wasn't there. Clearly the audience didn't really care.

With Characters and Character Arcs:

"The protagonist is the hero."

Variation Explanation: Often the protagonist is a hero. But you can totally structure a story where the villain is the protagonist and the hero is the antagonist. The protagonist is just the lead character--she's the character we are following who is taking critical action. The protagonist is the main person the story is about. In Death Note, the villain, a mass murderer, is the protagonist. He's who the story is about, who the audience is following around. In contrast, those trying to catch him--the heroes--are the antagonists.

To take it a step further, many characters aren't simply "heroes" and "villains." Some are gray. Gray characters can be protagonists and antagonists.

Some popular story structures teach structure based on the idea that the protagonist is the hero--like The Hero's Journey and Save the Cat!, and I admit that I myself sometimes use "protagonist" and "hero" interchangeably, mainly because I don't want to keep repeating the word "protagonist" and make my writing style sound clunky (but maybe I should kick the habit). And most of the time, the protagonist is a hero of sorts (has a positive arc).

But the fact that other structures often refer to the protagonist as the hero, is why I wanted to address this in this post. Many, if not most, protagonists are heroes, but not all stories are structured so that the protagonist is a hero. And some are even structured so that the antagonist is the hero. An antagonist is simply the character in opposition to the protagonist.

"The protagonist must have a positive change character arc."

Variation Explanation: Many structures (looking at The Hero's Journey and Save the Cat! again) feature a positive change-arc character as the protagonist, which makes sense because that is what is most common. Usually the character starts out with some kind of flaw or misbelief, that they must overcome through the course of the story to be successful. But that is only one type of character arc.

Many people have divided up character arcs into different categories, but boiled down to their most basic mechanics, you have four options:

1. The character changes, and the change is positive. This means that the character started the story with something negative--a flaw or misbelief--and changed to something positive by the end. An example of this would be Marlin in Finding Nemo.

2. The character changes, and the change is negative. This means that the character started the story with something positive and changed to something negative by the end. An example of this would be Anakin in the Star Wars prequels.

3. The character remains steadfast--more or less the same at the beginning and at the end--in a positive way. This means that the character started the story as something positive and ended the story as the same sort of positive. An example of this would be Diana in Wonder Woman.

4. The character remains steadfast--more or less the same at the beginning and at the end--in a negative way. This means that the character started the story as something negative and ended the story as the same sort of negative. An example of this would be in the story of the "Ant & the Grasshopper" where the grasshopper fails to prepare.

But character arc can get more complex than that--that's just bare basics. You can learn more in my booklet on protagonists.

Because positive change-arc characters are the most common protagonists, much structural advice is geared toward them. And in truth, much of plot structure remains the same, regardless of what arc you are using. Some features may just be reversed. But it's important to keep in mind that many structural guides are aimed at helping you write positive change-arc protagonists specifically.

"Change protagonists are paired up with steadfast characters, and steadfast protagonists are paired up with change characters."

Variation Explanation: In many stories, the change-arc protagonist will be paired up with a steadfast/flat-arc character (the Influence Character) in an important relationship. In Finding Nemo, Marlin(change) is paired up with Dory(steadfast). In Toy Story, Woody(change) is paired up with Buzz Lightyear(steadfast). In The Greatest Showman, P. T.(change) is paired up with Charity(steadfast).

In stories that feature a steadfast protagonist, this will often be reversed. In The Quiet Place, Part II, Regan(steadfast) is paired with Emmett(change). In Moana, Moana(steadfast) is paired with Maui(change). In Princess Mononoke, Ashitaka(steadfast) is paired with San(change).

Dramatica Theory argues that the reason this happens is because a story needs both types of arcs present to feel "whole" or "complete" to the human mind.

But not all stories have these pairings so obviously. Sometimes change characters are paired up or put in groups. But usually when this happens, an "outsider" who is steadfast begins to interact with the group. For example, in Stranger Things, Eleven is the steadfast Influence Character for the group of boys.

Likewise, you may group together steadfast characters, but there will usually be someone interacting with the group that has a change arc. In Finding Neverland, most of the Davies family are steadfast characters like James, which is why his relationship with Peter (a change character) gets the most emphasis.

Sometimes the protagonist has little direct interaction with the character of the opposing arc, but the arc is still present in the story. Sometimes the arc is present in unobvious ways.

Consider Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets where the thematic argument is that one's choices are more important than what one naturally is (whether that's pureblood, half-blood, muggleborn, half-giant, house elf, Gryffindor, parselmouth, celebrity, squib, or what have you). At first glance, all the "good guys" seem to be steadfast in the belief that choices matter more than nature, while all the "bad guys" seem to be steadfast in the belief that nature matters more than choices. Do any of the key characters strongly embody a change arc? Does any key character really move from believing nature is most important at the beginning of the story to believing choices are most important at the end?

Some of the key characters, like Harry ("Maybe I should be in Slytherin") are tested, but they don't have a change arc. It had me scratching my head for a week, but incidentally, I just found it while putting this post together--it's more present in the book than the movie. But a side character, Justin, along with some other Hufflepuffs judge Harry based on the fact he's a parselmouth, and at the end, Justin comes around. Obvious? No. But present.

Sometimes the opposing arc isn't really in a person. In Glass, all the key characters are steadfast characters. But it's the world at large that ultimately embodies the change arc. They convince the world of the truth.

While often the two types of arcs are embodied in key characters, they don't have to be.

With Theme:

"Every story should have a strong theme."

Variation Explanation: If you've been following me for a while, you may recall that I consider character, plot, and theme to be the holy trinity of writing. Usually, almost everything should connect back into one of these three things.

But it's important to keep in mind that some stories emphasize some of those more than others. A thriller is going to emphasize plot more than character and theme. Literary fiction, on the other hand, will definitely favor character and theme over plot. And some stories will be pretty balanced between all three.

Some stories put little to no emphasis on theme. However, because all stories are saying something about life, I would argue that all stories still have a theme. The thematic argument may be something as simple as, "good ultimately overcomes evil," or "cheaters never prosper," as opposed to something more profound like, "our choices, not our abilities, determine who we really are." And that's okay. Some stories are just aimed at having fun.

But once again, I sometimes can't help but ask, would the story have been better with a little more emphasis on theme? Probably.

"The protagonist must start on the truth/theme or the lie/anti-theme."

Variation Explanation: At the basic level, a theme is really an argument between two opposing worldviews. The theme statement is the winning argument (the truth). But it must have an opposing argument. This is the anti-theme (the lie). The protagonist's character arc directly plays into the theme:

1. In a positive change arc, the protagonist will somehow tap into the lie/anti-theme at the beginning, and then embody the truth/theme at the end.

2. In a negative change arc, the protagonist will somehow tap into the truth/theme at the beginning, and then embody the lie/anti-theme at the end.

3. In a positive steadfast arc, the protagonist will tap into the truth/theme at the beginning, and then still embody the truth/theme at the end, despite having that belief tested through the middle.

4. In a negative steadfast arc, the protagonist will somehow tap into the lie/anti-theme at the beginning, and then still embody the lie/anti-theme at the end, despite being asked to change through the middle.

This is generally true. But not always.

Sometimes the protagonist starts unsure of either side of the argument. The character may start the story knowing each side, but be undecided on which side they believe or fit into. They may start already confused and conflicted. Is one's nature more important than one's choices? Or is one's choices more important than one's nature? They don't really know. They'll usually figure it out by the end.

Alternatively, sometimes the protagonist starts ignorant of either side of the argument. They may not have ever considered or encountered either side. They've never thought about whether or not nature is more important than choices, and don't seem to embody either perspective. They'll likely encounter the arguments by the end of the beginning.

The important thing to remember is that there are at least two sides to the thematic argument, and each side needs to be shown fairly.

"The protagonist understands the theme by the end segment (Act III, if you will)."

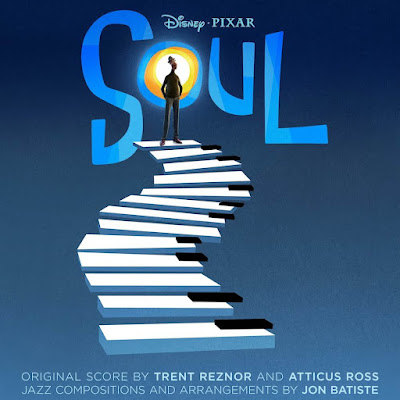

Variation Explanation: Usually after the Dark Night of the Soul lull, the protagonist learns something in a final turn that takes them to the climax. In a story with a strong theme, what they learn (or in some cases, regain) is often the thematic statement. In my earlier example of Old, the characters only figure out a plausible escape after they've learned to enjoy the present. In The Lion King, Simba re-embraces the Circle of Life and his role in it as the one true king. In Soul, Joe realizes that what makes life meaningful is the act of living itself. In Wonder Woman, Diana regains her faith that we should fight for the world we believe in. The thematic moment often leads to the character taking significant action

But in some stories, the protagonist doesn't understand the truth, the thematic statement, until the climax. Other times, the protagonist doesn't understand it until the denouement. Most Harry Potter installments are structured so that thematic understanding comes in the falling action. It's not until after Harry defeats Quirrel that he learns that his powers came from his mother's loving sacrifice. It's not until after destroying Tom Riddle's Diary does he fully regain the understanding that "It is our choices that show who we truly are." It's not until after he rescues Sirius Black with his patronus, does he understand that those who love us, never really leave us.

And in some cases, the protagonist may not really "understand" it, but still tap into, act on, or embody it.

"By the end, the thematic victory is clear."

Variation Explanation: As I said earlier, a theme is really an argument, which means it needs at least two sides. The climax and falling action will show which side of the argument is "correct," which side is victorious. However, in some stories, neither necessarily claims victory, leaving the audience to decide on their own which argument is better.

An example of this is A Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes by Suzanne Collins, where the outcome of the climax is ambiguous--one could argue between two different interpretations. Each interpretation leads to one side of the argument being the winner. This allows the story to simply explore each side of the argument and how they interact with one another. The audience gets to freely decide which side they believe in.

Sometimes the point isn't to argue which side is right, but simply to explore both sides.

"There is a primary theme and a secondary theme that interweave through the story."

Variation Explanation: Most stories will have more than one theme, but one theme is usually the primary theme and the others are more secondary. For example, in Finding Neverland the primary theme is that playfulness empowers us and helps us cope by getting us to believe in something bigger. And the secondary theme is that sincere friendship is more important than reputation.

But in some stories, there may be two themes that are handled more sequentially. In Pixar's Soul, the first thematic argument explored is about whether or not life is worth living. 22 doesn't believe life is worth living, and Joe knows it is. The second thematic argument explored is about what makes life worth living. Joe thinks if he doesn't succeed as a musician, his life will be meaningless. 22 helps him realize that what gives life meaning is living itself. There are really two thematic arguments being made, but one is emphasized more in the first half and the other is emphasized more in the second half (though of course there is some overlapping).

Likewise, in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), the first part of the movie is mostly an argument about purpose and meaning, and whether or not everything needs to have a point. This is embodied in lines like Charlie saying, "Candy doesn't have to have a point, that's why it's candy." And Willy Wonka's dad saying "Candy is a waste of time." And Mike Teavee asking, "Why is everything here pointless?" But later the film emphasizes the thematic statement that family is more important than success when Charlie turns down Wonka's offer so he can be with his family, and then later helps Wonka make up with his father.

I think this is probably tricky to pull off in a satisfying way, and probably wouldn't recommend it to most writers, but it is a variation.

"The external plot must be victorious for the theme to be victorious." (Or reversed if working with a negative arc.)

Variation Explanation: In most stories, the external plot will be a metaphor and vehicle for the theme. For example, in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Harry defeats the basilisk (which is killing people based on what they naturally are) with the sword of Gryffindor (which is symbolic of his choice to be in Gryffindor). So symbolically, the argument that what matters is our nature is being "killed" by the argument that what matters is our choices. Take this a step further, and Harry uses the basilisk fang to destroy Tom Riddle's diary, which is telling because Tom Riddle doesn't even perfectly embody his own argument--his father was a muggle. Harry didn't use the sword to destroy the diary. He used the basilisk.

But sometimes the thematic victory is realized mostly only on the internal plotline--the protagonist's internal journey. Thematically speaking, usually the protagonist coming to the truth, the theme, is more important than winning the plot goal. In contrast to Chamber of Secrets, consider Order of the Phoenix--none of the bad guys are really defeated, and Harry's actions actually lead to the death of one of the heroes. He doesn't really, obviously succeed in the main external plot. If anything, he played into the enemies' hands. The primary thematic argument is about whether it's better to go it alone so no one you love gets hurt (or can hurt you), or if it's better to find strength by involving those you love.

Externally, Harry's actions lead to the death of a loved one, and the near-deaths of many loved ones. Internally, he is able to defeat Voldemort's possession attempt by recalling the power and strength that comes from friends and family and love--showing that the bonds of love and friendship are worth the cost of pain and even death. This is cemented into place in the last line of the film, when Harry says, "There is one thing we have that Voldemort doesn't. Something worth fighting for"--i.e. loved ones.

He's not really victorious externally, but coming to the truth is more important, and more empowering. Furthermore, the fact the external plotline doesn't really end in victory, emphasizes that indeed involving loved ones has its costs--there are no guarantees, but it's worth the pain.

In some stories, the protagonist may even die in regards to the external plot, but if she has gained the truth, the thematic statement, she will not have died in vain.

In contrast, a protagonist with a negative arc could win everything externally--he could have all the world has to offer. But because he refuses to embrace the truth, the theme, his victory is hollow. In a sense, his soul is damned.

Now, with all that said, in some stories there is no internal plotline--in which case one of the other plotline types must prove the theme true--whether that's a relationship plotline, a world or society plotline, or simply the external plotline itself. The thematic victory in that plotline will need to be emphasized.

This could still get more complicated. For example, you might show each side of the thematic argument winning in different plotlines, which would make the theme more complex, but we are going to end here for today. Hopefully this list has helped you see that there are plenty of variations and rules you can break when it comes to structuring a story.

This was a fantastic post. I have been wondering about books that didn’t fall into the standard story structure and pacing.

ReplyDeleteThanks! I wish there were more lists like this, but maybe I'll add to mine as time goes on. We'll see. Thanks for commenting!

DeleteThis was absolutely fantastic! Thank you SO SO much for this post. I definitely need more resources on this topic so I'd LOVE to see two things:

ReplyDelete1) this list expanded as you update this post for a "2024 version"

2) you elaborate further on how The Hunger Games doesn't follow the beat percentages, how someone can pull that off, etc.

I'm so glad you liked and appreciated it (it was quite the feat to put together at the time 😆)

DeleteMulling this over, I think I have an idea for a post that will help satisfy both those requests (at least to some degree?? Not sure, but we will see!). It will probably take me longer to put together, but I think I can get working on it sometime soon.