Writing strong character relationships is critical for any author to master. Nearly every story, in nearly every genre, will feature a relationship for a plotline--whether that relationship is for the primary, secondary, tertiary, or quaternary plot, and whether that relationship is positive or negative, for allies, friends, love interests, coworkers, rivals, enemies, or what have you.

Set up the relationship dynamics right in your story, and any relationship will be easier to write.

Authors often use relationship plotlines because they fit exactly between the external plot and the internal plot. They aren't as broad and far-reaching as the external plot, but they aren't as deep or personal as the internal plot. This makes them a perfect fit to add dimension to any story.

Hello, everyone! I'm officially finishing up my relationship series (for now) with an overview of what we've covered. This page will work well to refresh you on the topic and help you find and recall any info you may need to come back to later. I hope this journey has been helpful to you, and I hope this page will help anyone new here, looking for a guide to writing relationships.

Please note for below: "Character A" and "Character B" may refer to either character in the relationship.

A Guide to Writing Relationships: 7 Comprehensive Steps

1. Identify the Characters' Relationship Arc

There are several basic types of relationships . . .

A relationship arc is how a relationship grows or changes through a story. Every significant character relationship can be broken down into four basic arc types:

Positive Change Relationship Arc

The characters start the story distant from each other. They are often strangers meeting for the first time, or they may even be downright enemies. But through the story, they grow closer in love and respect.

Examples: Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy in Pride and Prejudice, Sulley and Boo in Monsters Inc. Mulder and Scully in The X-Files.

Positive Steadfast Relationship Arc

In this relationship arc, the characters start already close and already have love and respect for each other. But through the story, their relationship is tested by the obstacles of the plot. They may have their rough patches, but ultimately, at the end, they stand by one another. They typically grow in their love and respect for one another.

Examples: Frodo and Sam in The Lord of the Rings, Harry and Dumbledore in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Peter Parker and his love interest in some of the Spider-man installments.

Negative Change Relationship Arc

The characters start the story close, with love and respect for one another. But they are ultimately pulled apart and become distant, as strangers or enemies. Often they grow in dislike or disrespect for each other.

Examples: Anakin and Obi-wan in Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, Katniss and Gale in The Hunger Games, Mike and Will in Stranger Things (Seasons 1 - 4)

Negative Steadfast Relationship Arc

In this relationship arc, the characters start distant--often as strangers or enemies--and end distant. They may be close for a time, through the middle of the story, but at the end, they don't stand by one another. Often their dislike and disrespect will grow by degree.

Examples: Winston and Julia in 1984, Angier and Borden in The Prestige, Estella and the Baronness in Cruella.

Beyond the basic relationship arcs, there are at least six variations.

It may be helpful to use more specific labels when mapping out your characters' relationship arc. For example: strangers --> enemies --> friends --> lovers

Your characters' relationship arc is one of the most important features to know in order to write a strong plotline for them. Know what direction they are growing, so you can write a great one.

Read more about Relationship Arcs

2. Turn the Relationship Arc into a Plot, through a Goal, Antagonist, Conflict, and Consequences

Having an entertaining or fiery relationship that arcs isn't enough to create a solid plotline. In order to be a plotline, the relationship needs a plot.

The primary principles of plot are goal, antagonist, conflict, and consequences. You can't have a strong plot without them.

Relationship Goal:

In a relationship, at the most basic level, there are only three goals: draw closer, grow apart, or maintain the relationship as is.

While other plotlines may influence the relationship plotline, when considering only the relationship one, ask, "How does my character feel about this other person? Does he want to draw closer to, grow apart from, or maintain things as is, with this other person?" That's the basic relationship goal.

However, it is likely the goal will change throughout the story.

Relationship Antagonist:

The antagonist is a form of opposition that is in the way of the goal. The antagonist can come from something external (outside the relationship), from within the relationship (the characters have differences that create obstacles), or from within a character (the character has internal conflict that is affecting the relationship).

At the basic level, the antagonist usually works like this:

If the character wants to draw closer, the antagonistic force is what's keeping them apart.

If the character wants to grow apart, the antagonistic force is what's pushing them closer.

If the character wants to maintain, then the antagonistic force is what's disrupting normal.

* Sometimes the antagonistic force is the other person in the relationship.

Many (if not most) weaknesses in relationship plotlines stem from weak antagonistic forces. Find the right, strong one, to make the characters' struggle believable (i.e. a simple misunderstanding that can be solved by a phone call probably isn't going to cut it).

Conflict:

The relationship goal and antagonist lead to conflict. There shouldn't be an easy, foreseeable way to fix this situation (if there is, the goal and/or antagonist isn't strong enough).

The more the characters want the relationship goal and the stronger the antagonistic force, the more powerful the conflict. How the characters address the conflict will usually create the arc. As the characters overcome, or are overcome by, the obstacles, they will draw closer or further apart.

Always remember the other plotlines may affect the relationship plotline.

Consequences:

Conflict without consequences is just cleverly disguised filler. Conflict should change outcomes. Consider: What do these characters have to gain (and/or lose) in overcoming the conflict? What do they have to lose (and/or gain) in being overcome by the conflict? What are the stakes and ramifications?

Ideally, the consequences of the relationship plotline will bleed into other plotlines. For example, if the characters can't work together, then the external plot goal can't be achieved. This is a common setup, but it's not the only setup. Likewise, consequences of other plotlines may affect the outcomes of the relationship plotline.

Read more about Relationship Goals, Antagonists, Conflicts, and Consequences

3. Strengthen the Relationship Plotline with Progress, Setbacks, Costs, and Turning Points

The secondary principles of plot are progress, setbacks, costs, and turning points. Make sure the relationship journey contains these.

Progress & Setbacks:

The audience dislikes when there is no sense of direction. To keep a relationship plotline from feeling aimless or like it is circling or stagnant, make sure there is progress toward the relationship goal and setbacks coming from the antagonistic force.

The relationship needs to be going somewhere, changing, as the characters are pushed closer or pulled apart. We want to create an ebb and flow, a zig-zag in the relationship. This is more impactful.

Costs:

Costs are what the character has to "pay" to move forward with the goal. The most meaningful costs come out of conflicts and consequences.

If a relationship has no costs, the characters didn't really have to struggle and sacrifice to be together (or, alternatively, apart). Costs are needed to show what the relationship actually means to the characters. As the plotline progresses, the costs should escalate.

The best dialogue, interactions, emotional responses, and physical descriptions will mean next to nothing if there is no proof or action behind them. Don't just tell us what the relationship means. Show us.

Turning Points:

In a relationship, a turning point happens when it becomes impossible for the relationship to go back to what it was previously. This will happen through an action (event) or a revelation (information).

Almost always, a relationship turning point will be marked with a moment of vulnerability, which is then accepted, rejected, or neglected by the other character:

Action or Revelation --> Character A's Vulnerability --> Accepted or Rejected (or, Neglected) by Character B.

The vulnerability may be voluntary or forced, and there are different types of vulnerability (psychological, professional, physical). Most relationships will have both positive and negative turns.

Escalate the turning points--the biggest turning point will happen at the climax of the relationship plotline.

Read more about Relationship Progress, Setbacks, Costs, and Turning Points (Sample)

4. Reinforce the Relationship Plotline with Plans, Gaps, and Crises

The tertiary principles of plot are plans, gaps, and crises.

Plans:

Having a plan reinforces the goal and a sense of progress. If the character truly wants something, they will have a plan to get it.

The character has a relationship goal. . . . How does the character plan to achieve that?

Gaps:

The gap is that space between what the character expects to happen and what actually does happen. The character has a goal and a plan and takes action, but sometimes reality delivers an unexpected outcome.

In relationships, look for situations where the character takes an action toward a relationship goal, but it backfires. For example, he may try to draw closer, but unknowingly pushes the other character away in the process (or vice versa).

Crises:

A crisis happens when a character has to make a choice between two opposing paths forward. They can't take both paths, and the choice is often difficult because there are stakes (consequences) tied to each path. The crisis is almost always sandwiched between two mini-turning points. For relationships, this is where it's usually found as well.

In a relationship turning point, something leads to Character A being vulnerable. This puts Character B in a crisis about how to react. If B accepts, then X will happen. If B rejects, then Y will happen. If B neglects, then Z will happen. It usually looks like this:

Action or Revelation --> Character A's Vulnerability --> Crisis --> Accepted or Rejected (or, Neglected) by Character B.

What Character B chooses will reveal true character and also arc the relationship.

Read more about Relationship Plans, Gaps, and Crises. (Sample)

5. Structure Your Relationship Plotline Correctly

Now that you know the arc and plot elements, it's time to organize them into a structure.

Because relationship plots can take so many different forms, it's important to understand the foundational principles behind their structure. This will allow you to properly structure any relationship plotline.

Some relationships start in Act I, while others start in Act II. You can have a relationship plotline that stretches over three acts, two acts, or even one act. But if it is the most prominent plotline, it (likely) needs to stretch through all three acts.

Each act should have a major turning point in the relationship. This major turn will either push the characters closer or pull them further apart, usually in an irreversible way. Map out the push and pull of the acts through your story. (Keep in mind the relationship plotline may be influenced by other plotlines.)

Between each major turn, there is a journey that can be thought of as a three-step dance: two steps forward and one step back OR one step forward and two steps back. Dance the characters between each major turn. Note: Act-level inciting incidents are what kick off this dance.

If you used specific labels (ex. strangers --> enemies --> friends --> lovers), each of these will likely be separated by a major turning point.

Make sure the biggest relationship moments are the act-level turning points!

Read more about Structuring Relationship Plotlines. (Sample)

6. Familiarize Yourself with Common Key Beats

Most relationship plotlines will include six key moments. When you know them and understand their functions, you can use them or adapt them for your relationship plotline.

The Meet Cute:

The Meet Cute is the first time the audience sees the relationship characters on the page together (whether they already know each other or are meeting for the first time). Use this moment to convey where the characters stand currently with one another. Ideally, you should individualize your Meet Cute to introduce the central relationship.

The Meet Cute may or may not be the relationship plotline's inciting incident, depending on how it affects the story.

The Adhesion:

Something locks the relationship characters together in an irrevocable way. This can be external, within the relationship, or within one of the characters.

At this point, there will be both an "adhesive" and "repellant" in play--a force of push and a force of pull. The relationship goal and antagonist officially set up the main conflict.

The Token:

This is a moment where the characters draw real close, and it is often marked by a token of love and/or trust (such as a first kiss, sharing a secret, or a rescue). This moves the relationship closer than it has been before in the story.

Usually, Character A will have an intensely vulnerable moment, that Character B will then accept and often even reciprocate.

The Breakup:

More or less the opposite of The Token, The Breakup pulls the characters further apart than before. Often one or both characters will be personally hurt (frequently from a form of rejection) and push away to protect themselves (or the other person).

Occasionally, in stories where the relationship plotline isn't the main plotline, the characters may simply be physically separated.

The Grand Gesture:

At the climax of the relationship plotline, Character A will have her most vulnerable moment. This will then be accepted or rejected or neglected by Character B in a defining way that completes the relationship arc.

This is often a moment where Character A lays it all on the table and stands figuratively naked before Character B. Like The Token, it is often marked by a grand gesture of either love/trust or hate/distrust.

The Denouement:

Use this beat to validate how the relationship has changed and/or remained the same--validate the completion of the relationship arc. Hint at a new normal for these characters. Show how the relationship changed or didn't change each individual character.

Read more about Key Beats in Relationships.

7. Flesh Out the Relationship

With the most important pieces in place, you can further flesh out the relationship.

A. Familiarize yourself with the role of the Influence Character--this is often the person the protagonist has a central relationship with.

The Influence Character has power based on influence (or in some cases, is the one being influenced by the protagonist). Usually the Influence Character will embody a different kind of arc than the protagonist. If the protagonist has a change arc, the Influence Character will have a steadfast arc. If the protagonist has a steadfast arc, the Influence Character will have a change arc (generally speaking).

The protagonist and Influence Character are often somehow linked together in the plot or are on similar journeys. However, because they have different worldviews, they have different methodologies, so they may argue about how best to move forward.

B. Check out some of the key features that make relationships irresistible.

Great relationships have a sense of history. And usually, the characters know each other too well. The participants should be opposites in some way that is relevant to the story. And they should probably show some form of affection (assuming they don't hate each other for the entire story).

If you are writing about a relationship that is already established before the story begins, you might want to employ these methods: communicate what's normal, imply an off-page history, have one character predict how the other will behave, give a sense of how the relationship has changed, round out likeness with foiling and opposition with likeness.

BONUS: Structure Your Relationship Arcs & Plots Through a Series

If you are writing a series, you may be wondering how to handle relationship arcs and plots through multiple installments.

You have a few ways to view relationship plotlines through a series:

1. Each installment has a self-contained relationship plotline . . . that progresses an overarching series relationship plotline.

2. Each installment essentially has a "standalone" relationship plotline.

3. There is one relationship plotline stretched over the whole series.

It's also possible to have some situations that seem to fit in between these.

One of the first questions to ask yourself is, "Are you plotting about the same character relationship?"

It's possible to write about a different relationship for each installment.

If you are writing about the same relationship, you may have a few restrictions and challenges. You might be limited on what arc you can choose, and you'll need to find a way to keep the push and pull in the relationship believable and interesting.

It's also possible to pull relationships from the background into the foreground, or push relationships from the foreground to the background.

Read more about Structuring a Relationship in a Series.

With all these things to explore, you'll be writing strong character relationships for any story, any genre, and any pair of characters.

Happy Shipping ;)

More Recommended Resources

The Relationship Thesaurus at Writers Helping Writers

Romancing the Beat by Gwen Hayes

***

Special Reminder: I'm Teaching a New Writing Course!

Craft your best book by focusing on what matters most: The “bones” of story.

This content-focused course will help you:

- Brainstorm better and more relevant material

- Evaluate what ideas most belong in your story (preventing you from writing hundreds of pages that need to be scrapped), and

- Craft a page-turning plot with compelling characters that sticks with readers long after they’ve closed the book (. . . and hopefully leads them to preorder your next book).

- And more

If you’ve found yourself writing and rewriting the same scenes, acts, or arcs, only to make them marginally better; or have struggled creating complex characters who are engaged in meaningful plots; or if you’ve been experiencing writer’s block over what you need to write next and how… The Triarchy Method will show you how to write a stronger, solid story by focusing on the “bones” of the story.

Character

Character is represented by the rib cage—it houses the heart of story. It’s how the audience gains emotional experience from the narrative, through (to some degree) empathy.

Plot

Plot is represented by the backbone—it holds the story upright and together. It’s the curvature that makes up the narrative arc, the spine that runs from beginning to end.

Theme

Theme is represented by the skull—it hosts the intellect of story. It’s how the audience gleans meaning that sticks with them long after the narrative is over. It’s why the story matters.

This live, online class is limited to 10 students and will focus on the core principles of each of the “bones” and how to structure them. Classes start March 7 and run Tuesdays and Thursdays at 6:30 pm Mountain Time (8:30pm EST) for a total of 23 classes. Classes ends on May 25.

For more information, visit https://mystorydoctor.com/the-triarchy-method-of-story/

***

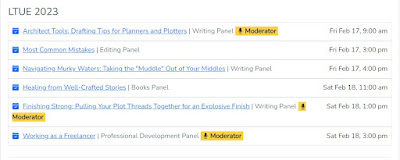

Special Reminder (x2): I will be at LTUE this Week!

I'm heading to Provo, Utah this week to be a panelist and moderator at LTUE. If you are going and would like to see any of my panels, click this picture to see it bigger:

***

Special Announcement: I will be Teaching at Storymakers this May

I will also be at Storymakers this May--the class will be both in-person and available online. It is called: "Be Ye Steadfast and Immovable": Writing Protagonists without Change Arcs.

Learn more about the Storymakers Conference here.

Whew! That is like . . . three more special announcements/reminders than I usually do. ;)

hi

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete