Developing a relationship plotline requires more than the relationship itself. It requires more than a relationship arc. It needs the proper elements of plot in place, otherwise it's not really a relationship plot.

Whether the relationship plot in your story is about love interests, friends, coworkers, mentor and mentee, rivals, or even enemies, and whether it's the A Story, B Story, C Story, or even D Story, it needs to have the proper pieces to be a real Story.

The primary principles of plot are goal, antagonist, conflict, and consequences. Last time, I covered how to apply these to relationships.

The relationship goal will be one of three things: draw closer and/or get along with this person, push away and/or cause dysfunction with this person, or maintain the relationship as is.

The antagonistic force will be what is in the way of the goal. If the character wants to draw closer to the other person, the antagonist pushes them away. If the character wants to be apart from this person, the antagonist pushes them together. If the character wants to maintain the relationship as is, the antagonist is what's disrupting "normal." In some cases, the other character in the relationship is the antagonist.

With the goal and the antagonistic force, the relationship plotline will have conflict. How the characters choose to address the conflict will usually create the arc.

And the conflicts only matter in that they have consequences. What do these characters have to gain or lose in being close? Or in being distant? Often the relationship consequences will affect other plotlines, or vice versa.

Today we will continue talking about relationship plot elements, by covering the secondary principles of plot: progress, setbacks, costs, and turning points.

For a more in-depth explanation of these elements in general, check out my article on the secondary principles of plot.

Below, we will apply these elements to relationship plots.

Progress & Setbacks in Relationship Plots

Once upon a time, I was reading a very popular series, and when I got to the last book, the central relationship started driving me crazy. Every time the heroine was with her boyfriend they argued and argued and argued, but it didn't feel like they were getting anywhere. Their situation was, more or less, the same as it had been from the first argument. This created a circling sensation, which I've talked about before. It happens when a plotline isn't really progressing in one direction or the other (experiencing setbacks). I got to the point where I wished they would just break up. At least then things would be changing and evolving (or devolving).

In short, the relationship plotline wasn't experiencing any real progress or new setbacks. It was just hitting the same conflict over and over. . . .

. . . Remember what I've said in the past: Conflict without consequences is just cleverly disguised filler.

Just as with other plotlines, the relationship plotline needs to be changing, at least a little. As the characters are facing conflicts, they should either be growing closer or apart. . . .

(Register for The Triarchy Method for full information)

Costs in Relationship Plots

Costs are what the character has to "pay" to move forward on the journey toward the goal. This may be physical and mental well-being, time, money, resources, or what have you. The most effective costs come out of the conflicts and consequences of the plot (as opposed to being random bad luck). This reinforces character agency and responsibility, which makes these costs more meaningful (and painful). (Read more about that here.)

While costs are important in any plotline, they can be particularly important in a relationship plotline. If a relationship has no costs, the characters didn't really have to struggle and sacrifice to be together (or, alternatively, apart), and it's the struggle and sacrifice that leads to a powerful relationship arc. The relationship isn't deep, meaningful, or personal without that. It's just surface-level. And the more difficult the journey, the sweeter the triumph.

Generally speaking anyway. (Yes, as I always say, there are always exceptions.)

In any case, we don't want this journey--this relationship--to be built on nothing. Only by showing costs and sacrifices do we truly convey what this relationship means to the character. Pain-free relationships are easy. Pain-full? That is the refiner's fire. . . .

(Register for The Triarchy Method for full information)

Turning Points in Relationship Plots

I've said this a lot on my blog, but just in case you are new around here, I'll say it again:

A turning point works by (you guessed it) turning the direction of the plot.

This can only happen one of two ways (well, or both of them): a revelation, or an action.

These are the only two ways to turn a plot.

Another way to look at them though, is . . .

Revelation = Information

Action = Event

Sometimes that is more helpful.

In a relationship plotline, think of this as a "Point of No Return."

Let me explain.

At the most basic level, the character is either growing closer to this other person, or apart. (And if they want to maintain, something will disrupt that, so they will still be either drawing closer or further apart to try to get back to "normal.")

In a relationship, a turning point happens when it becomes impossible for the relationship to truly go back to what it was previously. The characters may try to go back, but it's never really the same. You can't undo a reveal. You can't undo an action.

For example, in Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Darcy shares he's in love with Elizabeth . . .

(Register for The Triarchy Method for full information)

Relationship Turning Points: Vulnerability and Reaction

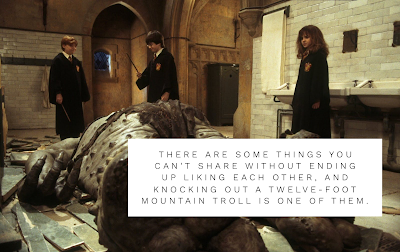

The turning point usually includes a moment of vulnerability. Mr. Darcy is being vulnerable by proposing to Elizabeth. Hermione opens herself up to punishment by covering for the boys. Scully has to risk the awkwardness or pain that might come if Mulder rejects her plea. Saying Obi-wan needs to die puts Obi-wan at more risk. And Gale has to tearfully apologize to the woman he loves.

Notice, too, that the reaction to the vulnerability moves the direction of the relationship. Elizabeth pushes Darcy away. Harry and Ron are shocked, pleased, and accepting of Hermione's sacrifice. Mulder agrees to Scully's offer (I mean, can you get much closer than being a possible baby daddy?). Anakin concedes Obi-wan must die. And Katniss rejects Gale. . . .

. . . The moment works like this:

Action or Revelation --> Character A's Vulnerability --> Accepted or Rejected (or, Neglected) by Character B.

Because of an action(event) or revelation(information), Character A has a vulnerable moment. Character B gets to decide to accept it, reject it, or in some cases, neglect it (that last one isn't usually as powerful--I also think you can argue it's still a form of rejection, but I decided to mention it since it is a little different). That (often) creates the relationship turning point. . . .

(Register for The Triarchy Method for full information)

Voluntary Vulnerability vs. Forced Vulnerability

In my earlier examples, Mr. Darcy and Scully are willingly vulnerable in front of Elizabeth and Mulder. They chose to put themselves on the line.

But vulnerable moments can be forced upon Character A, by external forces, other people, or even Character B. . . .

(Register for The Triarchy Method for full information)

Continue to "Writing Relationships into Plots: Tertiary Principles" (Sample) -->

Related Articles

Writing Relationship Arcs into Plots (Part 1)

The Secondary Principles of Plot: Progress, Setbacks, Costs, Turning Points

The 4 Basic Types of Relationship Arcs

Writing the Influence Character

Read Other Resources on Relationships

The Relationship Arc by Ross Hartmann at Kiingo

Romancing the Beat by Gwen Hayes

Sully or Sulley. Consistency please.

ReplyDeleteHey there, I'm not finding any instances of "Sully" in my articles. Is that what you were referring to? Or am I missing something? (I do admit that "Scully" does look similar to "Sulley," but those are two different characters.) (I would love to fix any errors I'm "blind" to or missed.) :)

Delete