I haven't ever done an article on in medias res in part because it's been covered so much in the writing world already, what could I really add to it that you probably haven't heard? Well, after looking around online . . . it turns out, quite a few things. I sometimes feel that in medias res gets misunderstood, and overused.

As most people who teach about in medias res will tell you within four seconds, "in medias res" is Latin that translates to "in the midst of things." In some ways, this is pretty straightforward: Instead of starting a story with exposition or setup, you start with the action or conflict. Most people will cite that this will grab the reader and draw them into the story.

As someone who has read thousands of unpublished manuscript openings though, I'll tell you that a lot of times, it doesn't. But I'm getting ahead of myself, let me backtrack a bit (speaking of starting something in the "middle of things" 😉)

Back when I was a "young" writer, when the topic came up of how to start a story, it was often, if not almost immediately, followed up by talking about in medias res. "If you don't know how to start the story, start in medias res"--I was told time and again.

So like many people, I thought that if I had bombs going off or someone dying in the first paragraph, that it would for sure hook the audience and get them to keep reading--and it'd be a great opening too!

Years later, when navigating submission piles, it soon became apparent to me that this often wasn't the best way to start. I could only handle so many "bombs going off" (metaphorically or literally) and "war battles" (metaphorically or literally), and I could only handle them for so long . . . before they got boring. (And to add to it, often newer writers, in their efforts to make it "exciting," make it unnecessarily graphic to the point of being grotesque.)

In contrast to what many people teach, in medias res can actually get rather boring within paragraphs or pages if it isn't done well. Because in medias res means cutting off the exposition and setup, it also means cutting off the context. If I have no clue who to care about, how we got here, and why what is happening matters, it can be really difficult to get invested in the story. After reading several paragraphs of people being run through with swords, I start wondering, Why does this matter? And why do I care?

And immediately teaching about in medias res when someone asks how to start a story often isn't a great way to teach how to start a story. After all--you're actually cutting off the starting of the story.

Of course, like anything, beginning in medias res can be great when done well and for the right effect. But in order to do that, you need to understand how it actually works and what that effect is.

For starters, it's helpful to not think of in medias res as only being used for story openings. You can use in medias res for any scene at any point in the story. So let's talk about how this works on the scene level, and then talk about it on the narrative level.

In Medias Res in Scenes

Typically, a scene is defined as a unit of action that takes place in a single location and continuous time. But this definition is certainly not perfect and the boundaries can get blurry fast with the right examples. However, I think most can agree that a scene is one of the smallest recognized structural units in a story.

And all structural units--whether they're a scene, sequence, act, or whole story--fit into this shape:

A scene will usually start with a hook and setup, followed by rising action (conflict), a climax, and a falling action. In some cases, some of these may be left out, but scenes almost always contain these things.

You can find slightly different approaches to scene structure from different sources.

For example, recently, I talked about scene structure according to Dwight V. Swain, who is famous for his approach. (In fact, his approach may arguably be the most famous.)

He recognizes two types of the smallest structural unit: scene and sequel (you can learn about them in more detail in "Scene Structure According to Swain" and "Sequel Structure According to Swain.")

The scene is made up of three parts: goal, conflict, and disaster. And the sequel is also made up of three parts: reaction, dilemma, decision. But regardless, both still fit into the structure above.

In medias res means "in the midst of things," so instead of starting with the hook and setup, you drop the audience right into the rising action, or in some cases, even climax. (And the conflict or climax often becomes the hook.)

The setup portion is used to ground the audience in the scene--it conveys when and where the scene takes place, who is in the scene, the character's goal, may lay out the stakes, and if there are multiple viewpoint characters, will clue the audience into whose viewpoint they are in. (For more on all this and scene openings, see "4 Key Elements of Scene Openings.") This orients the reader and gives context for what is about to happen. It gives meaning to the rising action.

When you start in medias res, the audience lacks this context.

In this way, beginning in medias res is a lot like writing a teaser, which also works off a lack of context. In a teaser, the whole point is to tease the audience through a lack of context. The teaser promises that if the audience keeps reading, they will get more context to understand what just happened. This is often a great way to use in medias res.

But just like a teaser, the audience won't stick around if context is withheld from them for too long. Like me going through submission piles, they start wondering, Why does this matter? And why should I care? Teasers only work well when they are short.

So, when you start in medias res, the audience can only handle so much of being "in the midst of things" before getting antsy for information. Contrary to what many writing instructors might advise, I would argue that starting in medias res is often harder, because the writer must fill the audience in on everything they are missing--and they must do it sooner rather than later. And often for newer writers, this leads to big dumps of information, setting, worldbuilding, characterization, stakes, goals--and whatever else--in the middle of conflict and action. Or, it might lead to the dreaded flashback. This is a tough situation to be in, even for the best of us, because one small reason that stuff is in the setup is so it doesn't clutter and kill the pacing of the conflict. It's so we can focus on the conflict.

Sure, some context will be easy to squeeze into the rising action. For example, you can convey the viewpoint character rather quickly. In fact, you can slip in most information in a line or two if you are well-practiced. But the problem is, it's often a line or two per thing: goal, character, stakes, setting, motive, and any other background info. That's a tall order.

Now, with all that said, you may think I'm against starting in medias res. I'm not. I'm just pointing out how difficult it can be, especially for newer writers, and yet we are often telling them to do it. I mean, no wonder beginning writers have so many flashbacks and info-dumps in their openings--they're being (indirectly) led to do that.

In medias res can work great in a few situations:

As a teaser: As stated above, starting in medias res is a lot like writing a teaser. The audience doesn't know the full context, and that's the point. The promise is that they will get more information if they keep reading, so instead of being drawn into the story because of the goals, stakes, and conflict, they are drawn into the story because of mystery, intrigue, and curiosity. The tone of the story is often conveyed, cluing the audience into what sort of emotions they can expect if they stick around. The audience won't stick around for long without important context, so the scene either needs to be brief, or the text needs to start filling the audience in after teasing them.

The setup information doesn't really matter: Sometimes how the character got to the rising action of the scene isn't really important to the story. For example, a story may open with a sword fight in medias res, but the fight doesn't really matter that much to the actual plot. It might instead be used to showcase the protagonist. Reading about a sword fight with no context can get boring. Reading about a sword fight told through a strong viewpoint character can be fascinating. And if he does a lot of sword fighting and is skilled in it, this might be an excellent way to illustrate that. You will of course still need to fill in some setup. But because the conflict itself isn't vital, you won't need to struggle explaining everything that led to this moment.

Other times the conflict does matter because the result kicks the plot in a new trajectory by affecting what happens next, but the setup isn't important because it's simple, mundane, obvious, or easily implied. It doesn't really need to take up that space to set the stage. For example, say we have a scene where some kids are playing hide-and-seek in the woods and one finds a treasure chest. The setup (which would involve starting the game) may not be very important. So instead, we might start with the "seeker" already finding one or two kids. Finding the treasure will be the scene's turning point, and change the direction of the plot as the kids decide what to do with the coins and jewels.

The audience already knows the setup: If you are writing about a famous event, such as 9/11 or Lincoln's assassination, you may not need to include the setup--the audience already knows what led to the conflict or climactic moment.

Other than that, if the in medias res scene isn't the opening scene, then it's possible a prior scene already established enough of the setup. The audience knows the goal and stakes, the time and place, because it was stated or implied. So instead, we can cut right to the action.

With all this said, almost no scene requires you start in medias res. So rather than stress if a scene should start in medias res, ask yourself if starting in medias res is more effective for the story you want tell.

In Medias Res in Narrative Arcs

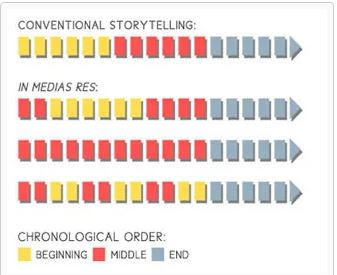

Because all structural units follow the same shape . . .

. . . you can essentially do this to the story as a whole.

The setup of a whole story covers about everything prior to the inciting incident. The inciting incident is a disruption that kicks off the plot of the story and is either a problem or an opportunity for the protagonist. The setup introduces us to the characters, setting, and establishes a sense of what's normal.

While uncommon, it's not impossible to start the story with the inciting incident. It's even technically possible to start a story after the inciting incident. However, I hesitate to go too deep into that, because I think the terminology and definition can get blurry and gray pretty fast. Nonetheless, it wasn't uncommon in literature of the past to cut the beginnings and endings off short stories, with the idea that a strong middle will imply both the beginning and the ending.

If your opening scene includes the inciting incident or takes place after the inciting incident, you'll likely need to introduce the characters, setting, goals, motives, and stakes afterward as the story progresses--unless most of that prior to the inciting incident isn't really important to the story (which rarely is the case). This information can be filled in through flashbacks, dialogue, and narration. Like with scenes, this can be a tall order, because we don't want to lose the sense of immediacy or slow down the story with info-dumps. With that said, you often have to fill in some backstory regardless of where the story opens in the narrative arc. It's just that in medias res, you'll likely need to fill in more and be more careful and clever about it.

A more common approach is to take a scene from the rising action or climax of the story and insert it at the beginning. This works as a sort of teaser for the audience. An obvious example of this happens in Twilight, where Stephenie Meyer takes a passage from the climax and puts it at the beginning of the story as a short preface. The story will then go back and start the setup. The teaser draws the audience in, and as they get to the setup, they wonder how the character ends up in the later situation.

Sometimes the scene is strictly plot driven, such as someone finding a dead body, a victim who was clearly murdered. When the story goes back to the setup, the audience wonders what led to that moment. Who killed that person? And why? They'll now be watching for "clues" as the story goes back to the beginning.

In order to pull this off well, the teaserly scene should not spoil the actual story. I've heard of a t.v. show that did just that--actually spoiled the whole build up in the first episode. Of course, you didn't realize that until you got closer to the climax--and by then, what's the point if you already know the answer to the questions being posed?

In any case, just as with the other section, starting a story with any narrative in medias res can create a sense of mystery and intrigue, by stirring up curiosity. This is because the audience lacks full context. Like with teasers, they'll now be watching and waiting for the context.

However, unlike with in medias res scenes, in narrative in medias res, the audience is willing to wait longer for the context of the story as a whole. They understand the moment comes from later in the narrative. As long as they have scene-level context quickly--so they can actually enjoy and follow the story--they'll be willing to take the journey to get narrative-level answers.

To be honest, I don't see many novels or short stories that open in narrative in medias res. It's something I feel is more common to film. And in a way, the second type, where you take a scene and plug it in at the beginning, can sorta feel like cheating, but it can work well in stories that have a calm setup and slower rising action. By teasing what comes later, you get the audience to stick around. And the contrast between high stakes or tension and then a calm beginning can often be intriguing. It certainly can be done well.

And of course, if you want the audience to be on the lookout for "clues," then it might be a great way to start too.

Just like scene-level in medias res, narrative in medias res is rarely required. Ask yourself if starting in medias res is more effective for your story.

|

| Check out this great in medias res diagram from TV Tropes |

Opening in Medias Res (Among Other Things)

As stated above, when people talk about in medias res, it's usually in reference to the opening of a story. This is done either on the scene level or on the narrative level.

Your opening scene may skip its setup and start right with the conflict.

Or, the opening scene may come directly from the rising action or climax of the whole story.

Arguably, you can look at in medias res in other ways as well--just as there are scene level and narrative level ways to execute it, there are arguably sequence levels and act levels. One may argue that an important backstory (such as the protagonist's "ghost" or "wound") also has its own narrative arc, and a story may open with a prologue "in medias res" of that narrative arc. But that's all more intense (and confusing) than what I want to go into for now.

Also, like with many writing terms, not everyone views in medias res the exact same way. There are slightly different definitions and interpretations of it floating around. But hopefully this article gave you a more defined understanding of how it actually works and when to use it.

Thanks September, for another well thought through article.

ReplyDeleteThanks for visiting, Charlotte, and commenting!

Delete