Anonymous asked: Hi, I visit your tumblr frequently. Creative writing is my passion and I am learning a lot reading your posts. I have also read books about screenplay (and the book by Lisa Cron about how our brain works). I love writing fantasy young adult novels but for me it's hard to outline. Could you give me some tips? :-) (Forgive me for my grammar errors. English is not my first. language) :-) Thank you so much. When you publish your novel, I will love to read it :D

Hi anonymous,

Well, talking about outlining can be a little tricky because just as people write differently, people outline differently. For creative writing, there aren't a lot of rules for how you outline. Some writers don't outline at all. They simple start writing and find their story as they go. Personally, I'm a big outliner, but I also leave myself some room in case I come up with better idea along the way.

Now, for some, when they talk about outlining, they simply mean planning things out ahead of time, and how and what to plan, but others mean the actual physical process of outlining (physically writing down and organizing their outline), so I'll try to talk about both.

What to Outline (Planning and Plotting)

The one thing every outline should probably have (literally drawn or at least embodied in the story structure) and you probably already know about, is the Freytag Pyramid.

There are a few different ways to look at plot, but this is the most basic.

You can get a little more structured, like in this image of the three-act structure.

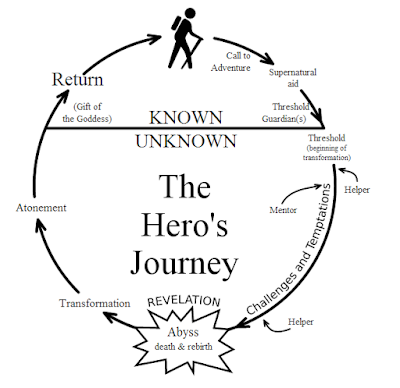

There is also the famous Hero's Journey story structure

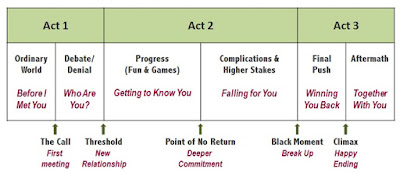

A romance story might have it like this

(Some writers put in that "Fun & Games" section, such as Blake Snyder in Save the Cat.)

You can find many different story structures, but all of them, even the Hero's Journey must still follow the Freytag triangle to be effective.

There is a time period in literature (an attitude that still prevails in some places even today) where people argued that stories shouldn't really have a structure, because life has no meaning, and therefore your stories shouldn't follow the Freytag triangle. Cool, you can do that if you want, but don't expect too much of a readership. The truth is, most people don't like stories like that, and the truth is, life has meaning because we give it meaning. And even in life, there are rising actions and climaxes and denouements. One of the reasons people like stories is because they embody the concept of giving life meaning.

A good idea may be to study novels in your genre or that at least have similar structures to the structure you want.

Story Parts

The Very Beginning

Often what happens before the inciting incident (discussed below) is meant to ground the reader into a sense of normalcy in the story. Often it serves as an introduction. If your story takes place in another world, you need to clue the reader into what kind of world. Are we in space? The 1920's? Oxford in a parallel universe? Who is the protagonist? What is their life like right now? It's hard to nail down a catch-all for this section, because every time I think of a requirement, I think of stories that are exceptions. For example, some writers say the opening scene must introduce the readers to the important players of the story, but in a hero's journey story, that likely won't be the case. But the point of this section is probably to prep for the inciting incident by grounding the reader in a sense of normalcy. In some stories that get to the inciting incident very quickly, some of this grounding info will come in alongside it or even after it.

With all that said, however, there are some things you should absolutely be aware of in the opening of your story. And I've covered that in a few other places:

Tips on Starting a Story

How to Write a Good First Sentence

Many writers consider the beginning section of the novel the most difficult to write because it must accomplish so many things while hooking and grounding the reader--and it must do all this flawlessly.

The Inciting Incident

The inciting incident is the point where your protagonist starts off in a new direction or encounters a problem. Some say this must be "the big problem" of your story, but that is not always the case. Look at Spider-Man. The inciting incident isn't that Peter runs into a villain. In fact, in quite a few Spider-Man movies, he doesn't encounter the super-villain until much later. The inciting incident is that he gets bitten by a radioactive spider. This works well, because the movies are just as much (if not more) about Peter Parker living with his super abilities as they are about him defeating villains.

Some inciting incidents are pretty indirect and can happen across several moments, instead of one. What is the inciting incident of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone? It might be hard for some to say right away, after all, Harry doesn't make a decision to even do something active about the Sorcerer's Stone until halfway through the book. But like Spider-Man, if you look at the Harry Potter books, they are just as much about what it's like being a young wizard learning in the wizarding world as they are about an antagonistic conflict and mystery. So the inciting incident is instead the process of Harry learning he's a wizard. It's similar to Peter Parker, but it seems more stretched out. The ball gets rolling with the first letter Harry receives; in fact, this section has its own rising action (in contrast, Peter Parker's sort of comes out of nowhere). But if you had to pinpoint one moment, it's when Harry hears that he's a wizard. That changes everything.

Some inciting incidents or more direct and obvious. In The Hunger Games, the inciting incident is when Prim gets picked for the Hunger Games and then Katniss volunteers to take her place.

In these examples, it might be worth noting how the inciting incident gives you an idea for what kind of story you are in for. In The Hobbit, the inciting incident is when Bilbo is called to go on an adventure. And what kind of story is The Hobbit? It's an adventure/journey story.

The Rising Action (The Middle)

While many writers say the beginning is the most difficult to write, others say the middle is the worst. Often this happens because writers have an idea of how their story starts and how it ends, but are not sure how to get from one point to another. Since the middle is the longest section of the story, it can't be saggy and needs to hold the reader. As the name suggests, everything needs to rise.

New York Times best-selling writer David Farland, has these wise words to share about dealing with the middle: the story either broadens or deepens--or does both.

A story that broadens means the conflicts and stakes reach and affect more people or places or things. Everything gets bigger and wider. So maybe your story starts with one murder. If your story broadens, it grows to include more victims or the pool of potential victims gets bigger. More people are at risk.

If the story deepens, it means it becomes more significant and personal to the protagonist. If your story starts with a murder, your protagonist might realize the criminal is actually his childhood best friend.

The best stories usually broaden and deepen. In a murder story, your protagonist may realize a serial killer is targeting teenage Christians girls (the conflict broadens beyond that of one murder), and she has daughter who fits that description, knew the other victims, and may be at risk (the conflict deepens).

There are some plot devices, tropes, or techniques you can use to really intensify the rising action. The important thing is to raise the stakes--to broaden or deepen the problems.

As I mentioned before, some writers add a section called the "Fun & Games" section. "Fun & Games" may not necessarily be that relevant to the plot, but it's just what it sounds like--it's a section catered just to entertaining the audience. Blake Snyder, a screenwriters says that this section showcases the reason people come to the movie (or pick up the book).

For example, people saw Elf because they wanted to see a human who was raised by Santa's elves try to navigate in New York City. People went to My Big Fat Greek Wedding because they wanted to see the entertaining antics that come with trying to plan and have a wedding when you have a big Greek family. In an action movie, this might be a section where we see crazy action scenes; maybe the audience came to see the protagonist blow things up. The "Fun & Games" section is usually the section that gets shown in movie trailers.

The Midpoint

Some structures mention the midpoint (others don't). The midpoint is where everything changes. Usually, new information enters the story that changes everything. Other times, it's not so much new information as it is a context shift. The protagonist might be sitting down to eat and suddenly see everything that is happening from a different perspective, leading to a big (or deep) realization. Something suddenly clicks into place that changes how they view or approach the problem.

The midpoint in Interstellar is when Cooper realizes that Plan A, to save those living on Earth, was just a ploy to get him to go into space, and in reality, he'd unknowingly abandoned those people to their deaths (broad), including his own children (deepen). It's new information that changes context and therefore changes everything.

Climax

In the climax, the main conflict reaches its peak, and the protagonist deals with it head on. She may have dealt with it head on before, but not quite like this. New information has entered the story. Or she's overcome a weakness that now enables her to take a stronger course. Or maybe she has a new idea.

It might sound ironic to readers, but often the climax is the easiest part to write. The author has been thinking about it a lot, and it's mainly composed of finally dealing with conflicts that have already been grown and established. It's a matter of resolving conflict after conflict, tying up loose end after loose end.

In Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, the climax is Harry going through the trapdoor to confront Snape (who then turns out to be Quirrell and Voldemort).

Often in the climax, there is what is called a reversal, a point where it seems the protagonist is going to lose, but then at the last instance, gets a sudden idea and is able to turn the tables. In Sorcerer's Stone, this is probably where Harry realizes his body has magical properties against Voldemort and is able to burn him using only his hands.

The main thing with the climax is that it delivers--it (almost always) needs to be more intense, more emotional, more significant than what came before.

Why "almost always"? Because I believe some stories are exceptions--particularly comedy. In the Diary of the Wimpy Kid movies, the best parts are usually the Fun & Games. In comedies, the climax usually deals with more serious matters; the reason for this is because if we get humor for an hour and a half straight, we usually become numb to it. Almost all comedies that are longer than an hour or longer than a short story have to throw in a serious string of plot points. This is because you have to contrast the emotions in order to keep them sharp.

You can read more about that concept here: Gaining Incredible Emotional Power by Crossing Opposites

You have to have something serious to keep things funny. In Enchanted, the beginning and middle probably give us the biggest emotional high as opposed to the climax and denouement. Sure, the emotions are more serious, but I argue they still don't reach the same height as the humor.

So it does depend on the story you are telling.

But still, usually the climax needs to be what hits the audience most powerfully. The audience needs to have a payoff for everything they sat and read through up to this point. It's the moment where the protagonist confronts the antagonist once and for all. It's the moment where a couple resolves their problems and fully confess (or re-confess in some cases) their love for one another and decide to be married. It's the final battle to storm the castle.

Denouement

The denouement or falling action is what happens after the climax. It gives us a sense of what has changed (and in some cases, what hasn't), since the beginning of the story. Any remaining side conflicts are resolved, loose ends tied up, or still-needed explanations given (some exceptions to this if the story is a part of a series). It gives us a glimpse of a new normal, or maybe in a series, a promise of what will happen next. There is a saying in the writing community, that comes from crime novelist Mickey Spillane: "The first chapter sells the book; the last chapter sells the next book."

This is true for any book, series or not. If it's a series, it sells the next installment. If it's not, it leaves people wanting to buy the next book you write.

The denouement must show and prove to us that there was payoff from the climax. The couple who confessed their love must get married or at least be shown being in a committed relationship. Evil is defeated in Middle-earth (whether at large, or in the Shire), and the hobbits get to sing and dance back home. In Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Hagrid is released from Azkaban, there is a great feast, and of course, Gryffindor wins the House Cup. Katniss survives the Hunger Games and returns home to Prim. Problems have been resolved.

But while you may have a denouement that focuses on a "happy ever after," other stories may have a denouement that leaves the protagonist "sadder, but wiser"--the protagonists aren't happy per se, but they learned valuable lessons, and so did we as an audience. At the end of The Hunger Games series, Katniss is left broken, Prim is gone, and her relationship with Gale in unrepairable; the society she fought so hard for (when she'd never wanted to, to begin with) is still somewhat infected with evil desires. Katniss and the audience are sadder but are wiser because of the valuable lessons about human nature that are learned.

However, you can have a denouement that does a little of both, which is usually a good option for "epic" stories. For example, while the denouement in The Hunger Games is tragic, there is still some goodness in it. Katniss finds love with Peeta. In the Epilogue, we learn that, no, there are no more Hunger Games. Their kids get to play in the fields. While damaged, both Katniss and Peeta helped change the world.

The same is true with The Lord of the Rings. While the hobbits get to dance and sing in the Shire, and Sam marries and has children, Frodo never fully recovers. Because of his experiences, the Shire can never be what it once was to him. He is unable to return to the old life he yearned so much for and never wanted to leave to begin with. So we get some heartbreak through him and when he leaves his dear friends, especially Sam, to go to the Grey Havens.

Bittersweet endings are great for epic stories, or stories with significant teachings and thematic points. Happily ever after endings or great for light-hearted stories. In some cases, with stories that deal with dark subject matter, the "sadder but wiser" story is the best route to drive home a point--but keep in mind that it will always anger some audience members.

In rare cases, some stories don't have a denouement or if they do, it's a very short one. Some short stories can get away with this, but 99% of the time, if you want to write an emotionally successful story, you want a decent denouement. After spending a novel with your characters, your audience probably wants to know what happens to them, what their life will be like now. The denouement is a great place for reflection. It's a moment to take in all that the character and audience have been through and what they learned or gained. If something tragic happened, it's a great moment for crying. If much was won, it's a great moment for happiness and celebrating.

More Resources

You can go far deeper into all this than I have, which is why there are whole books written on it. Two books I very much recommend are Million Dollar Outlines by David Farland, and Story Engineering by Larry Brooks.

Other Elements

There are of course, other things to plan and outline besides the plot. You'll need to figure out your cast of characters, character arcs (how the character(s) grows and changes through the course of the story), the setting, and maybe some themes (and how those will be illustrated).

If your setting is historical, you'll need to do research and figure out where these places will fit in or how they impact your story. If it's fantasy or science fiction, you'll need to do some worldbuilding. And if it's contemporary . . . you may also have to do some research.

Some people believe you should not outline the themes ahead of time because it makes them feel stiff, formulaic, or preachy. While I certainly believe you do not have to outline them ahead of time, I certainly don't believe you should never. I think some great writers can absolutely outline them ahead of time and know how not to make them stiff or preachy.

But all of these things could be their own topics, and I've already done a lot on characters on my blog.

Some Important Advice

When it comes to talking about all this, it's important to remember, as I mentioned at the beginning, that there are a number of different story structures. Some people in the writing world only have eyes for one, and then they go on to compare all other stories to that one story structure. Not every story has a Hero's Journey structure. Some people do not know about or understand the Fun & Games section, so they might say you need to cut it. Others might argue that the climax in your comedy needs to be louder and bigger than your comedy beats. Some writers believe you must follow Blake Snyder's beat sheet.

All of these structures are meant to help us write better stories, not worse. Beware of trying to make your story fit a structure it isn't meant to. When in doubt, study successful stories similar to what you are trying to accomplish, trust your vision, and cover the basics: beginning, rising action, climax, falling action/denouement.

Next Time

Whew, as you can probably guess, that took longer for me to go through than I expected. I'll continue more next time, talking more about how to outline, now that we have covered a bit about what to outline.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

I love comments :)