Theme is one of those elusive words that people often use but don't fully understand in storytelling. Worse yet, there are actually a lot of misunderstandings in the writing industry and community about it.

Here's the deal: Whatever we write communicates or teaches something to the audience, whether or not we intend it to.

During His ministry, Jesus Christ used parables (aka, stories) to teach people lessons, morals, new ideas, and change culture and ideology. Whether or not you are Christian, you've likely heard of the parable of the Good Samaritan. What is the point of that story? What is it teaching? It's teaching that we should love, be kind to, and serve everyone--regardless of nationality, religious background, culture, or whatever. Everyone is our "neighbor."

A thematic statement is essentially the teaching of a story. So for the Good Samaritan, the thematic statement is, "We should love, be kind to, and serve everyone."

Let's look at some other famous stories and their thematic statements (teachings).

The Little Red Hen: If you don't contribute or work, you don't get the rewards of those efforts.

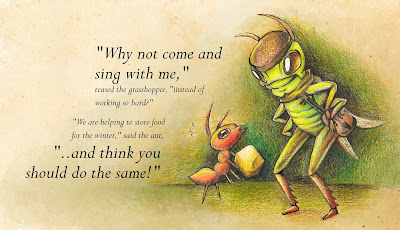

The Ant and the Grasshopper: If all we do is have fun and entertain ourselves, we won't be prepared for difficult times.

The Tortoise and the Hare: It's better to move forward at a steady pace than go so fast we burn ourselves out.

These are old, famous fables with seemingly obvious thematic statements. Often in children stories, the theme is stated more directly. For adult fiction, it may be much more subtle.

Here are some more modern examples.

The Greatest Showman: You don't need to be accepted and loved by the world, only by a few people who become your family

Spider-verse: If you get up every time you get knocked down, you'll accomplish more than you thought possible

Harry Potter: Love is the most powerful force in the world

Zootopia: To change biases in society, you first must evaluate and work on your own biases.

Les Miserables: Mercy is more powerful than justice

Legally Blonde: Someone who is beautiful, blond, and ultra-feminine can be smart and taken seriously.

Hamilton: We have no control over our legacy.

(By the way, I realize a reuse a lot of the same examples on my blog, but it's just faster and easier than grabbing something new. What matters is that you understand the concept, regardless of example.)

|

| Thematic statement: You don't need to be accepted and loved by the world, only by a few people who become your family |

Okay, so when we take English, language arts, and literature classes, we are usually just taught about thematic statements.

Which makes it difficult when you are trying to create stories, because if that's the only thing we understand about theme, and we try to write with that in mind, we often come off as sounding "preachy." As a result, many seasoned writers have actually told themselves and others not to write with any theme in mind (which has its own potential problems that I'll talk about later).

A good portion of this next section is information that comes from Amanda Rawson Hill and K. M. Weiland, because they are the two people who got me to have a clearer, conscious understanding of theme.

Okay, so we have the thematic statement, but on a broader scope, we have a theme topic. The subject or topic about which something is taught. It's the concept, without the teaching attached. It's what the theme or story is "about," in an abstract sense.

Here are the theme topics of those stories:

The Little Red Hen: Contribution and work

The Ant and the Grasshopper: Preparation

The Tortoise and the Hare: Pacing

The Greatest Showman: Acceptance

Spider-verse: Perseverance

Harry Potter: Love

Zootopia: Bias

Les Miserables: Mercy (and justice)

Legally Blonde: Being respected/taken seriously

Hamilton: Legacy

The theme topic is broader than the statement. The thematic statement is the specific teaching about that topic.

Note: People often use the word "theme" to mean either "thematic statement" OR "theme topic," which is why it can be confusing. I've done this multiple times myself, but am trying to stop. (Plus the fact my ideas on storytelling are regularly evolving, probably doesn't always help with ambiguity on my blog either)

|

| Theme topic: Perseverance |

In a strong story, the theme topic will be explored during the narrative, through plot or character or both. The story will ask (directly or indirectly) questions about the theme topic. This can happen through main characters and main plots, or side characters and subplots, or all of the above.

Let's look at some examples to illustrate what I mean.

In The Little Red Hen the theme topics of contribution and work are explored by having the red hen ask multiple characters for help (or, in other words, for contribution and work) and by having the red hen work alone. She herself is asking questions related to the topic.

In The Tortoise and the Hare, the theme topic of pacing is explored and questioned by comparing a slow character to a fast character, and as the plot unfolds, we see the choices each one makes.

In Zootopia, the theme topic of bias is explored, as a prey animal cop (the rabbit) has to interact and team up with a predator criminal (the fox), and each have biases against the other. But the theme topic is also explored in the society as a whole. Officer Hopps is told by society that she can never be a cop. Nick is told by society that because he's a fox, he must be untrustworthy. In one scenario, Hopps is trying to overcome her society's bias. In the other, Nick has given into society's bias--he will only ever be seen as a fox. Side characters and subplots explore the topic of bias as well, whether it's pitting crime on predators or dealing with nudist communities. Everywhere, the theme topic of bias is being touched on. By exploring the topic from all these different sources and perspectives, the audience is naturally confronted with questions (whether or not they are consciously aware of this). Can you succeed in a biased society, or will a biased society keep you from ever becoming what you want? In our efforts to create an unbiased society, do we criticize others' biases while remaining blind to our own? How can we create a safe, unbiased community? Are we prejudice ourselves?

Pretty deep stuff to be asking in a kid show, right? Disney is a pro at handling theme in their animated movies, so they are definitely one I'd recommend for people who want to study well done examples.

In The Greatest Showman, the theme topic of acceptance via love is explored in a similar way. As a child, P. T. Barnum is never accepted or loved by his society. His goal in life is to give the girl he loves an extravagant lifestyle, to prove to her parents, nay, to the whole world that he's worth something. Through the course of the story, he tries to do this in multiple ways: at his job, he approaches his boss with a new idea; he tries to start a museum; he starts a circus; he wants to present an opera singer to the world so that he can gain notoriety. Everywhere, the protagonist is asking for love and acceptance, and it's never enough.

But side characters and subplots explore this topic as well. Charles doesn't want to be laughed at for being small, Lettie doesn't want to be a freak for having a beard, Anne doesn't like being treated differently for being black, Phillip wants to leave high society but will be shunned, Jenny Lind never feels good enough because she comes from a low class. As we see these characters collide with other characters, and society, we are confronted with questions. Can these people ever find love and acceptance? Will they ever feel fulfilled? How can they overcome society's hate and prejudices? Are they willing to sacrifice family, income, security, personal weaknesses to get there? And furthermore, it seems that as you are finally accepted by one group of people, your are only rejected by another--can you be accepted by all circles? And does it matter if you aren't?

Often when writers fail at theme it is because they are only focused on the thematic statement. And they are therefore not fairly exploring and questioning the theme topic.

But the theme statement is the answer to the exploration and questioning, and should not be fully realized until the end.

|

| The theme topic of pacing is explored by comparing two characters |

Let's take this a step further. We have the thematic statement. We have the theme topic. But in most stories, the beginning will have or illustrate a false thematic statement. (Alternatively, K. M. Weiland calls this "The Lie Your Character Believes.") This is almost always manifested through the protagonist in some way.

The false thematic statement is typically opposite of the thematic statement.

The Ant and the Grasshopper: The grasshopper believes that all he needs to do is have fun and entertain himself, and he doesn't need to work or prepare--that's a waste of time. OR "Having fun is more important than preparing."

The Tortoise and the Hare: The hare believes if he runs as fast as he can, he will easily win the tortoise. OR "If I go as fast as I can, I'll be most successful."

The Greatest Showman: P. T. Barnum believes if he shows the world how amazing and successful he can be, he'll be loved and accepted by all society. OR "Once you prove you are amazing, all of society will love and accept you."

Spider-verse: Miles Morales believes that by quitting everything, he won't have to deal with any expectations. OR "If I don't persevere, I don't have to worry about expectations."

Harry Potter: Because his parents are dead, Harry Potter begins as an unloved and powerless person living in a closet. OR "Death and oppression are the most powerful forces in the world."

Zootopia: Judy Hopps believes she will fight society's biases by proving to everyone else that a bunny can be a cop. OR "To change biases in society, you must start by criticizing everyone else's."

Les Miserables: Jean Valjean was thrown in prison for nineteen years for stealing a loaf of bread and when released continues to deal with extreme justice, which leads him to stealing from the church. OR "Justice is more powerful than mercy."

Hamilton: Hamilton believes he will create and build and control his legacy by never throwing away his shot. OR "If I seize every opportunity to be great, then I will leave a powerful legacy after I'm gone."

You'll notice I left out the Little Red Hen. Her story is different. From the beginning, the little red hen believes in the thematic statement--that's why she is working so hard, but the theme topic is still explored and questioned (and tested) through her interactions with the other characters. This can be done in modern stories too, but it's rarer and harder to pull off. Remember, I said writers often fail at theme when they only focus on the thematic statement, without fairly exploring or questioning the topic. In The Little Red Hen, it's all the other characters that embody the false thematic statement. They think they can enjoy the rewards without having done any work. Take note that the red hen herself isn't preachy or snooty. She adheres to her beliefs, even though it requires more of her (because no one will help, she has to do more work).

In order for stories like this to be successful, we need to see the protagonist have to struggle through more adversity to adhere to the true thematic statement. Remember how the maxim goes, "No good deed goes unpunished." These stories are more difficult to write, so I probably wouldn't recommend them to beginners, but I'm not going to say no definitively. If your protagonist starts with the true thematic statement, she still needs to struggle, if not struggle more.

Legally Blonde is similar. Elle Woods fully believes she can get into law school and get her boyfriend Warner back, despite everyone around her saying Harvard won't take someone like her seriously. Throughout the movie, Elle is constantly told she just isn't "serious" enough. However, her story varies from the red hen's, because as the theme gets questioned and explored she eventually reaches a point (at Plot Point 2), where she succumbs to the idea that no one will truly respect her, when she says something along the lines of, "All people will ever see of me is a blonde with big boobs. No one will ever take me seriously. Not even my parents." But once she receives her "final piece to the puzzle," she returns to and proves the thematic statement that someone can be beautiful, ultra-feminine and smart, respected, and taken seriously.

So the Little Red Hen and Legally Blonde are rarer variations, but keep in mind that they still legitimately question, explore, and test the theme topic (this is key).

|

| False theme statement: To change biases in society, you must start by criticizing everyone else's |

In most stories, the protagonist starts with the false theme statement and ends with the (true) theme statement, a process that typically comes about through the main character arc. (You can read more about this specifically here).

So here is how the theme may fit in, in story structure.

Beginning:

Protagonist believes or illustrates the false thematic statement.

Middle:

The theme topic is explored through plot and characters having different experiences and providing different outlooks.

This will lead to questioning: It leads to the audience questioning. In most stories, it leads to the protagonist questioning. After all, he believes in the false thematic statement, and maybe after these encounters, he's unsure how true it is.

(Also worth noting, the middle may test and disprove wrong thematic statements other characters have.)

The middle is the "struggle" part of the theme, and on Freytag's Pyramid, the rising action. We are struggling to come to a better understanding of the theme topic.

At the second plot point, the protagonist may have an epiphany (the true thematic statement) or at least a turning point, where they now take on, embody, or demonstrate the true thematic statement.

Note: In some rare stories, the protagonist may not embody the true thematic statement, which will result in a tragic end for them. If the thematic statement is true, then they can't "survive" (literally or figuratively) if they don't learn to adhere to it. (If they "survive," that means that what you thought the true thematic statement was, was probably just another false thematic statement, and you got them mixed up somewhere.)

Note: Also, the true thematic statement may be stated prior to the ending, but the protagonist will not fully realize or embody it until the end.

Ending:

The climax of the story is the ultimate test of the final, true thematic statement--does it hold up to the test? Is it proven to be true? If it's the true thematic statement, it must.

In the denouement, the true thematic statement is further validated. We proved it true in the climax, now we must validate and show its effects. This can be very brief--one example--or it can be validated again and again through multiple examples.

It's worth mentioning, too, that in a lot of highly successful stories, the antagonist embodies THE false theme statement or A false theme statement (which is one of the reasons why they fail). So Voldemort can never understand that love is more powerful than death and oppression (notice that Voldemort and Harry have similar beginnings in life). In Les Mis, Javert ultimately can't live with the fact that mercy is proven to be more powerful than justice (which is why he takes his own life). However, this tactic is not a necessity by any means, just something worth considering.

|

| As the antagonist, Javert can't survive the true thematic statement |

Now does everyone who writes successful stories consciously know and adhere to all the things I've talked about so far in this article?

Heck. No.

Remember the first of this, where I said even seasoned writers may believe you should write with no theme in mind?

Lots of people write successful stories without even thinking about a theme.

But.

If you are aware of how theme functions, you can use that to an advantage and write even more powerful stories (and it will help you stand out from those that don't).

There are lots of stories that are good that don't follow through on this element of story structure--but I sometimes wonder: How much better and stronger could they have been if they did?

Theme is what makes a story "timeless." This is exactly why Christ's parables and Aesop's fables have withstood the test of time. Why audiences trust Disney movies for a worthwhile emotional and intellectual experience every new movie. Why classics like Les Mis or Shakespeare are still taught and studied today. Because they aren't just stories. They are perspectives on the human experience and teachings that influence lifestyle and culture. They can touch hearts and minds and shift ideology.

And even if you write a story without caring two cents about theme, it will still have a thematic statement. Because every story is teaching something--if only through action and character. But there are dangers and problems that can happen (especially in today's world), if you don't pay attention to theme at all. Take the famous children's story, The Rainbow Fish. I loved that book as a kid (and if you aren't familiar with the story, you can listen to it here), but it has problematic, unintentional teachings. It teaches that in order to have friends, you must give away personal boundaries; that you can "buy" friends; that if you want to be liked by others, you need to give them things they ask you for. Sure, it conveys that sharing makes you happier, but it has those problematic parts as well.

Did the writer intend to teach those negative things? Probably not. But in the story, they are "proven" as true thematic statements simply because of the outcome of the plot and characters.

|

| Typically the protagonist moves from a false thematic statement to the true thematic statement |

This could get all into some really deep stuff, like minority representation, biases, culture control, and censorship, but for today, let's leave that for the university classrooms. (Not to mention, for someone learning the craft of writing, it can sometimes feel super paralyzing.)

I will say that even in stories where the writer doesn't completely care for or understand theme, even if the thematic statement is good, I sometimes find myself wondering if the theme is "underdeveloped." But that doesn't mean I still can't enjoy and support the story.

For most writers, theme isn't going to make or break your ability to get published. It's not something I would tell beginning writers to stress out about straight out of the gate. But it is something that can move you from great to phenomenal.

You don't need to know your theme topic or thematic statement to start writing. I would wager, that the majority of writers don't. Often what happens is that a theme topic or thematic statement will start to naturally emerge. Then in the revision process, you can use this article to check, develop, and strengthen the theme.

You can have more than one theme. As you are writing, you may realize that there is more than one theme topic and thematic statement. Lots of stories have more than one. Like I talked about in my story structure series, Spider-verse also has themes about choice and expectations. Harry Potter is chock-full of themes. Legally Blonde includes thematic statements about having faith in people. In some cases, one theme will relate and play into another or help refine it. With all that said, there is usually one theme that emerge as the main theme.

And that's pretty much what's worth knowing about writing your story's theme.

|

| "First impressions aren't always correct. You must always have faith in people. And you must have faith in yourself." |

0 comments:

Post a Comment

I love comments :)