1 - Pick a Theme that Fits the Story.

To

some, this may sound obvious, but once in a while writers try to fit in

a theme that doesn’t actually naturally fit into the story they want to

tell, which can make it feel off and wooden in the text. It’s like a

puzzle piece in the wrong puzzle box.

A lot of stories will actually naturally hint at a theme just in their premise. More on that here.

Some

stories have more wiggle room, but since theme needs to come out of the

story, not be forced on it, the contents of the story need to suit it.

2 - Utilize this Robert McKee Exercise.

One of the problems with addressing theme, is that often teachers teach us the end result/conclusion of the theme, instead of all the other moving parts.

They teach us the thematic statement. But theme itself is broader. It explores a theme topic.

Thematic statement: Love conquers all.

Theme topic: Love

Once you have a topic, you can do this exercise that Robert McKee came up with (you can learn about it and how to do it here.)

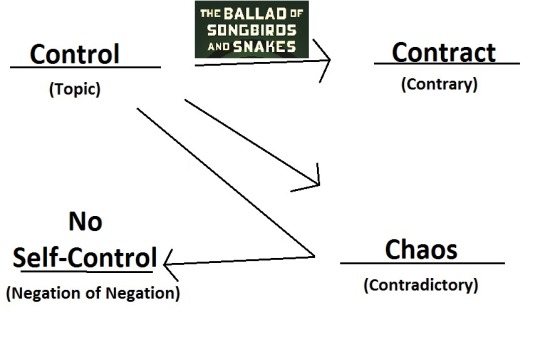

Some of you may have seen my recent rendition of it for Songbirds and Snakes:

This

will give you at least three other topics to play with. It may give you

more, because more than one answer may fit each blank.

This may also bring up other secondary theme topics, as the opposite of “control” is also “freedom.” And another contrary of control and chaos is “trust” (these are both secondary themes in that book.)

If you

want, you can then take secondary theme topics, and do this exercise

again (the contradictory of trust is distrust, etc.) But I don’t want to

get too complicated.

Now that you have four elements, you’ll

look for ways to adequately and fairly illustrate and explore them in

the story through the plot and characters.

In a sense, these

topics are sort of in an argument or power struggle with each

other--make sure to include and look at gray situations. One of the

most common problems I see is when the writer tries to portray

everything as black and white (control is always the “best,” for example), but life

is more complex, so it falls flat because it doesn’t ring true to the audience.

When you come up with ideas for the story, or you are brainstorming, pull this out and look for ways to possibly touch on one or more of these subjects (that’s what helps me anyway). It’s not always about telling and stating them--it’s most often about “showing” them to the audience.

So

in one of my WIPs, the theme topic is authenticity. So recently

as I was revising a section, I looked for ways authenticity, fake,

privacy, and being inauthentic within yourself, could be rendered in

that section.

Before you come to a conclusion as to the

“winner” of the power struggle, you need to “visit” with each

opponent--if that makes sense. So you need to touch on each of these

topics--that will make the thematic statement seem more "earned" and the experience of the story more fulfilling for the audience.

3 - Look at the Protagonist

(For some people it may be helpful to do this before the exercise above.)

Most protagonists will have a character arc--meaning they will grow and change by the end of the story.

But

let me explain this another way. At the beginning of the story, the

protagonist has a flaw, weakness, or misbelief about the world that is

inaccurate. This will (most of the time), in some sense, be the opposite of the thematic statement.

Some quick examples from elsewhere on my blog:

Zootopia: Officer Hopps believes the problems with bias is in everyone else, and so she’s going to prove them wrong by being the first bunny cop.

In

reality, by the end, she grows and realizes she has her own biases she

needs to address. The thematic statement is, in order to defeat bias, we

have to start with the biases within ourselves.

Harry Potter:

Harry starts unloved and powerless in a cupboard under the stairs. By

the end, he learns he’s so loved, it can defeat the darkest wizard of

the wizarding world. The thematic statement is, love is the most

powerful force in the world, it conquers all.

You can learn more about this here.

So

the protagonist starts with an inaccurate worldview, and through the

story, that worldview is challenged and called into question. The

character will be pushed to reconsider his or her beliefs, and will have

to overcome a misbelief or flaw, to get to the true thematic statement.

Again, it’s critical that the story look at gray areas and situations, otherwise the transformation won’t ring true.

If the protagonist doesn’t flip a worldview or personal trait (which is rarer), instead they will have their accurate worldview tested by the environment.

It will be costly for the protagonist to adhere to this worldview

because of the pressure put on by the environment to try to get them to

change. By the end, the environment shifts its worldview to the correct thematic statement, not the character. (Legally Blonde is a good example of this).

Both approaches should be shown in the story, more than told to the audience. (Like anything, it's great to tell some parts of it, but you can't tell most of it)

And the true thematic statement should not be fully realized

until the ending segment of the story. The beginning should illustrate the

inaccurate worldview/problem. The middle should challenge that and

explore gray areas. The end will synthesize what has been learned and apply it to prove it true and validate it.

Also, you can learn a bit more on this here.

4. Look at Side Characters and Relationships

Just as the protagonist will touch on the theme topic, other key characters (usually those in a relationship with the protagonist) will as well. Look for interesting viewpoints and arguments the side characters can have about the theme topic.

In Hamilton, all the key

characters touch on the theme topic of legacy: Hamilton, Burr, Eliza,

Laurens & Hercules & Lafayette, and George Washington, even General Lee--but they

each have a slightly different viewpoint or experiences with legacy.

In Moana,

each key character touches on personal identity: Everyone on the island

says who they are right now and what they do every day on the island is

who they are, period; Maui’s entire identity is built around what others think of him, he thinks who he is, is what others think he is; Tamatoa’s identity is based on his appearance, his shiny

outside is who he is. Te Fiti has become a monster because her heart

was stolen, so she no longer knows who she is. Moana’s grandma helps

Moana see who she truly is.

Side characters and their stories and interactions often offer exaggerated, inverted, mirrored, or complex looks at the theme topic. These will often come into play in the middle of the story, illustrating that the theme topic is actually more complicated than the protagonist (or audience) first thought (therefore challenging and testing their inaccurate worldviews).

5. Look at the World and Society

Turning broader, in some stories it may be helpful to look at how the world or society touches on the theme topic.

For example, in Moana, Moana’s people have an inaccurate view of themselves, because Maui

stole the heart of Te Fiti, which consequently led to them being stuck

on an island. Therefore the only way to fix the problem is to restore

the heart so Te Fiti remembers who she is, which leads to Moana’s people

remembering who they are, which connects to their ancestors--another

group of people.

Consider, how can what is happening in the society or

world of the story illustrate the power struggle of the theme topic and

its counterparts?

In Les Mis, the theme topic is

mercy. Within the world and society, we see mercy and justice and

everything in between play out within France itself. Whether that’s

Fantine’s societal situation or the Master of the House, the young men trying to change the country, or the orphans on the streets.

6. Save the Best for Last

The

true thematic statement should only be fully realized and fully

illustrated by the hero at the end. The biggest mistake I see writers

make, is they pick a thematic statement, then swing it around

everywhere--beginning, middle, end and everything in between. It doesn’t

work because life isn’t like that.

The thematic statement is the manifestation of wisdom.

True wisdom is only gained by learning to reconcile life’s complexities (a.k.a. the grays). This means in order to reach true wisdom, we need to fairly explore and consider the grays of life. Only after the protagonist struggles through the grays and complexities, will the thematic statement feel “earned” and “true.”

Only after Moana

encounters everyone’s views of identity, is she able to come to the

wisdom of what identity actually is--what her identity actually is.

This moment usually happens at the end of the middle or the beginning of the end--then, the protagonist will implement what’s been gained, through the end. (Moana’s realization leads to her realization about Te Fiti, which sets everything right.) But I won’t get into structure too much here.

7. Judge Not

It’s

important not to “judge” or condemn your characters through most of the

story. This will make the theme feel flat and preachy.

When

we meet Maui and Tamatoa, the story doesn’t get preachy about how they

are wrong. Instead, the story simply lets them do them. It doesn’t need

to tell us they are wrong, because as natural consequences take place in the story, the narrative will illustrate that by the end.

Sure, the protagonist might pass judgement to an extent (Jean Valjean doesn’t like Javert in Les Mis), but it’s key to let the other characters simply play out their belief system. This relates to showing the theme, more than telling it.

When

you start trying to condemn a character in a text too early, it shifts

the tone and undercuts the power of the theme, because you aren’t

exploring each aspect fairly.

Only at the end, after

everything is fairly explored, can judgement (of some sort) be

passed--and this is often shown more than told. (Generally speaking, as

there are exceptions.)

For example, Javert can’t live with himself after Jean Valjean shows him mercy, so he takes his life. Obviously his belief system, which was fairly shown through the whole story, is wrong.

Voldemort, who shows no love, is boiled away by love into a wisp.

In the Lion King,

whose theme is about fulfilling your proper place in the “Circle of

Life,” shows hyenas attacking and killing Scar. Scar tried to upset the

Circle of Life, and now something perhaps more unnatural happens to

him--he’s being eaten by scavengers.

This works the other way too, as Simba is honored, restored, and accepted as true king.

Harry succeeds in defeating a dark wizard and is more loved and powerful by the end.

And Jean Valjean finds God’s grace in the afterlife.

But these are all more shown than told.

Telling is okay. You can say it straight out. As long as it’s shown more than told.

And

it’s better not to condemn your characters when exploring theme--let the

consequences of their choices and the story’s outcome do that on their

own. (In a sense, they condemn themselves.)

There are a couple of other things I could talk about, but I think I’ll leave it at that for now.

I guess I would say, look at whatever you are writing and . . .

A) If it’s the beginning,

consider how it can show a wrong or inaccurate worldview of the theme

topic. Or, another way to approach this is to look at “black &

white” views (in the beginning only). In Les Mis, mercy and justice are black & white concepts in the beginning. Harry Potter? Harry is hated and despised, while his nephew is loved to a fault. In Hamilton, Hamilton’s white view of legacy is contrasted by Burr’s black view of it.

B) If it’s in the middle, consider how you can bring in other views and opinions and gray situations related to the topic(s). (Like I talked about above with Moana and Hamilton). This will most likely include side characters and their stories. It will probably challenge or at least complicate the protagonist’s view of the topic.

C) If it’s the end, consider what can play out to illustrate the true thematic statement. Those who believe it should usually find some sort of reward. They will usually illustrate it in a key action. Those who don’t believe it will usually find some sort of defeat.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

I love comments :)