Stories are about cause and effect. That's what makes it a story. There is a famous example of this in the writing world:

"The king died, and then the queen died."

This is not a story. It's just stating what happened.

"The king died, and then the queen died of a broken heart."

That is a story. Why? Because it has cause and effect.

All great stories need to have some level of cause and effect. Otherwise, they aren't really stories. (Well, there are maybe some exceptions, but more on that later.) Readers don't want to read about random, unrelated things (most of the time); they want to read stories.

At the starting of a story, the main character should have (near-future) wants and fears. This helps draw the audience in by getting them to look forward to significant, potential consequences, or in others words, stakes. This also gives the character motivation for making choices.

When we make choices, they automatically lead to consequences.

- If I refuse to exercise, I won't have an athletic body.

- If I choose to eat a bunch of sugar, I'll get a sugar high.

. . . which means they have a cause and effect.

Not all causes and effects come from our own choices. We don't live in a void. There are other people who also make choices, there are illnesses, natural disasters, cultures and societies, the laws of physics, etc.

At the starting of the story, the main character is going about his or her life, making choices, until a cause (the inciting incident) challenges the established normal, calling the hero in a new direction. Cause and effect.

From that moment on, cause and effect will get more important in the story. Or at least, it should.

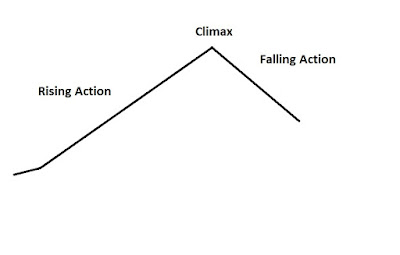

As a story goes on, the consequences and stakes should get bigger and bigger or more and more personal, so that we have that rising action or escalation, that is vital to a good narrative. If the consequences stay small, or even get smaller as the story progresses, it's not going to be a satisfying book. Never forget this most basic story shape:

Still, occasionally I run into manuscripts that are largely lacking a nice sense of cause and effect. Instead, they are just things happening. And I've sometimes found it missing within my own projects. Perhaps this concept seems so simple, that we never give it a second thought.

You see, too often as writers, we think in sequential events, not consequential effects.

Sure, you can escalate conflict without having cause and effect. Maybe in the beginning, your protagonist is sad she didn't get invited to a birthday party. Then in the middle she has to win a state sports competition. Then at the end, she finds out she has cancer. Technically, that is escalation. So it can be easy to fool yourself into thinking the story is gonna be great. (And then you'll likely be confused when it's not quite satisfying.)

Sure, unrelated conflicts like this can escalate. And the conflicts matter--in that moment, for that time. But because they don't tie into other things, they aren't as meaningful, they don't hold as much tension--hope and fear--or stakes. They can almost never draw the audience in as intensely, because the audience can't anticipate or care about what might come next--it's not connected.

So it's almost always better to escalate conflict by amplifying cause and effect. The protagonist is sad she didn't get invited to a birthday party, and so she plots revenge. Carrying out these plots reveals a new side of her to her friends and family, and so it strains their relationships, and so they plan an intervention, and so the protagonist gets sent to a youth camp she hates, and so . . . and onward.

It's sort of like the butterfly effect. One conflict kicks us off (the inciting incident), and through cause and effect, it builds and builds and builds until it's huge by the climax. That's what's satisfying.

As a Southpark creator teaches, writers shouldn't be saying "This happens, and then this happens." They should be saying, "This happens, and therefore this happens."

This gives the story a sense of cohesion. This is because cause and effect tie everything together. While hooks and stakes and tension get readers to look forward, and draw them in. Cause and effect is the bridge from immediate past, to present, to those futures--linking every event in a chain. When events are connected, the audience cares, because they can predict.

Ideally, each segment of the story is feeding into the next one, which is bigger. Each act in a story, is feeding into the next, bigger one. Personally, I like to think of it as a small fish feeding a bigger fish. Act I is the small fish, but it feeds and nourishes Act II, which is the medium fish, which feeds and nourishes Act III, which is the big fish. Or if you don't like to think of acts, think of it as the beginning, the middle, and the end. Each fish is swallowing up the smaller fish before it. The little fish feeds into the big fish.

All easier said than done.

BUT, the more you understand this, the easier it eventually becomes to brainstorm and structure a story. Because if everything is feeding into something else, then you are largely looking at how one cause leads to other effects, which are in turn causes to other effects, which are in turn causes to other effects--and on and on until you get to the climax. So it's not about just trying to come up with ideas from a blank page, it's about looking at what you already have for potential consequences.

In the process, you will find that there are multiple potential outcomes for the same event, so the question doesn't become "What do I have happen next?" It becomes "Which do I have happen next?"

In such cases, consider these things:

- Which effect is most interesting?

- Which effect carries the most meaning?

- Which effect carries the most tension?

- Which effect leads to the most future effects or the biggest problems?

- Which effect has the strongest connections to the other effects in play?

- Which effect is most relevant to the theme?

- Which effect best plays into the character arc?

- Which effect forces the most change or growth?

- Which effect best fits the story I'm telling?

Also, take into account the story structure you are using (if you are using one). It can guide you on what to pick. If it's time for me to have a pinch point, then I should pick the effect that fits as a great pinch point. If it's nearly time for The Ordeal, then I should pick the effect that leads into that.

It's funny, because often when we learn about such things, we don't want to feel "boxed in," but in reality, all of these things are just tools to help us navigate and make satisfying decisions, which leads to stronger stories. And better yet, they will actually lead you to brainstorm stronger, richer, more powerful ideas, leaving you to ask "Which happens next?" and not "What happens next?" Because the most effective brainstorming doesn't happen in a void. It happens when you have guidelines and pull from what you already know about your story. Because if anything can happen, then nothing really matters.

Cause and effect are key to satisfying stories--from the first bits of brainstorming, to tying up the loose ends during the denouement.

Consider: One Cause that Leads to Multiple Effects

It's also worth noting (and helpful) that one cause can actually lead to multiple effects in the story. For example, the inciting incident may affect each key character differently, leading them to make different choices, which lead to other effects. It need not always be one to one (one cause = one effect). In fact, often it's capitalizing on multiple, possible effects that makes a story more riveting, more of a page-turner. But even as you branch off from the same event, ideally, each of the effects are still going to play into, connect, and affect each other.

For example, in The Hunger Games, the Reaping in District 12 is the inciting incident, but it affects Katniss, Peeta, and even all of Panem, differently. Katniss decides she will do everything it takes to try to survive for her sister. Peeta tries to accept that he'll die, but he wants to die as himself--while doing all he can to keep Katniss alive. Katniss also can't wrap her head around the fact that she'll be in the arena with Peeta, who once saved her life. The Capitol is first impressed by these tributes, and then enamored with their "love story." What Katniss does, what Peeta does, and what the Capitol does all feed and connect into each other--leading up to the climax, which incorporates all these elements and affects each key player differently--what the Capitol views as an act of love, the Districts view as an act of defiance, Katniss views as an act of survival, and Peeta (also) views as an act of love, but just as importantly, an act that shows the Capitol can't change him--all of which affects the second book in the series, so their story continues to build . . . and build . . . and build.

Escalate cause and effect to satisfyingly escalate the conflicts.

Look for opportunities where one cause can lead to multiple, significant effects.

This sort of thing can be particularly key in writing sequels. Many sequels fall flat because they try to create something entirely new, instead of allowing what happened in the last book to feed into the cause and effect trajectory of the next book. They simply start a new thread, instead of allowing the end of the last book to have a ripple effect on the world. (This of course depends in part on the type of series you are writing.)

Possible Exceptions

In certain forms of highbrow literature, a lack of cause and effect is the point. Some people have argued that because life is random, stories should be random too, with just things happening and no real meaning. There is probably a place for that kind of outlook, but if you want to write commercial fiction or genre fiction (which is what my blog is pretty much all about), this is often a terrible approach. Also, while we don't have control over everything in real life, cause and effect is real. And our personal choices do have consequences.

Some types of stories need less cause and effect than others. Like perhaps in humorous slice-of-life stories. I think Napoleon Dynamite is a good example. A lot of it is just funny stuff happening. BUT, I bet if you watched it again today, you'd notice that there actually is a bit of a story structure to it, and some through threads of cause and effect. And if you do write this kind of story, it needs to be super entertaining for your target audience to be successful.

And many stories that don't seem to have much of a cause and effect in the plot, actually have powerful cause and effect in the character. As the plot happens, it effects how the character grows, so that she arcs in a significant way by the end. So the cause and effect mostly exists on a more personal level.

But, with that all said, the majority of stories will be more satisfying when they really utilize cause and effect on a plot level.

How Does this Affect the Writing Process?

It's funny, after I wrote a draft of this post, I read Story Genius by Lisa Cron (which I definitely recommend), and in it, she talks a lot about cause and effect (and nails it). But she said something I've personally felt for a while: The more you utilize cause and effect, the more you will likely need to write your story in order. Because if you are fully utilizing cause and effect, then what happens in the previous scene affects the next scene. Some writers like to jump around, writing whichever scene they want to, and then plug that scene in the appropriate spot, and take a pass at completion to link everything together. If that works for you, who am I to say it's wrong?

But for me, and the way I write, I admit I have found this confusing. How do I know all the effects a scene at the end of the book needs, when I haven't yet nailed the cause-and-effect trajectory of the middle? So I generally prefer to write down the ideas I have for future scenes, and maybe even snippets, but I don't really "write" them until I get there. Do what works for you, but I thought this was worth mentioning.

Jumping around between scenes can work. Just be prepared to go back and do a lot of rewriting later to make sure all the cause and effect makes sense. To be honest, that's the method I used when I wrote my Hogwarts fan fiction story. Admittedly, that was my very first story so I didn't have much of a clue about writing. And not having a clear idea of how all the scenes fit together is one of the reasons it took ten years to write the darn thing. Now I tend to write in chronological order.

ReplyDeleteYeah, I think it does take some revision and rewriting, but it obviously works well for some people. It sort of gets down to what I hear some writers say--you either "front load" the work or you "back load" the work. I tend to prefer to "front loading."

DeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete